QEII

The Queue

It’s a curious business, the death of a Queen.

Two weeks ago, London was a (fairly) regular place and, post-funeral, is (sort of) normal again. But for just over a week, it became somewhere entirely different: a strange griefopolis, at the center of a land baffled by sadness and doubt.

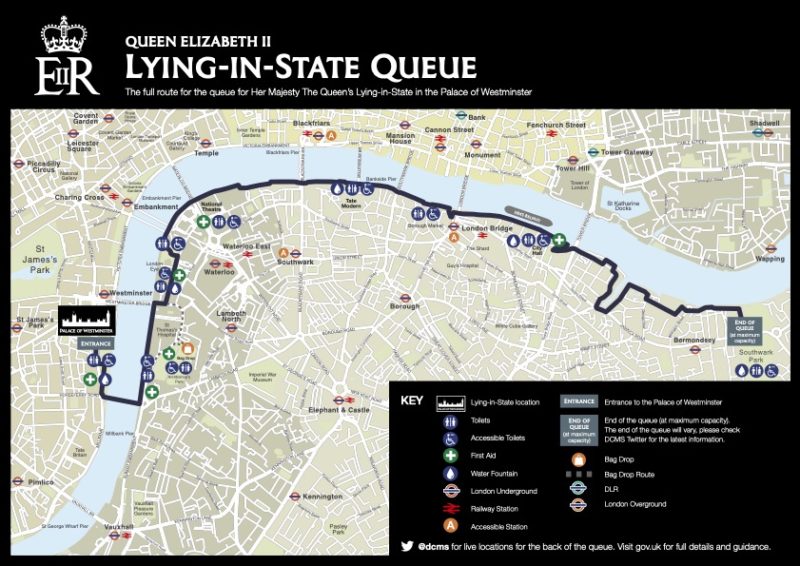

In the middle of it all, of course, was the Queen herself. To pay her formal respect meant joining a queue—the Queue—leading to Westminster Hall, where she lay in state. The Queue stretched several miles along the Thames and required between six and 20 hours of persistent shuffling to complete … an act of reverence fused with real physical endurance.

From the day of its opening, the Queue’s wild expansion (every hour brought more incredible updates about its growth) quickly became astonishing; the motives of its participants became increasingly incomprehensible.

Like nearly everyone I knew, I’d no plans to join them.

Then, waking early last Friday, I saw that by catching a bus near my flat, I could make it down before sunrise and be done by teatime. So—dreamily—I packed cheese sandwiches and set off. My intentions were blurred … I simply felt drawn. I hoped to discover why I’d gone when I got there … the Queue would tell me why I’d come.

Getting off my bus half a mile from the end, its pull was apparent. Pre-dawn streets were jammed with budding Queuers: Crowds jostling and bumping and gossiping out of London Bridge station, all trying to track down the Queue’s end and begin their day. There was a lot of faux-nonchalant jogging as thousands tried to find an ever-receding end, all of us discreetly chasing the end of an immensely serious conga line.

I saw the Queue for the first time at Tower Bridge (where those secure inside peered out at me with sympathy) but that was not the end. I joined a quarter of a mile downriver.

Then, once in, I could watch the people endlessly flooding past as they tried to get themselves to the back: determined couples in late middle-age; giggling students; men and women with military bearing (many sporting medals); some unexpected Goths; a few that looked like frat boys off for a week in Ibiza; hordes of cheerful grandmas.

Several children were apparently there against their will. “You’ll relish this memory,” shouted a mum to a skeptical tween, “for the REST of your LIFE.” Any reply was lost as they were both borne away on the mourning tide.

Then the business of the Queue began: that is, standing for long periods, then quickly moving. Then standing again. Then shuffling a bit. Repeated for hours.

The autumn air blew chilly off the river as we progressed (past the Globe and Tate Modern; the National Theatre and the London Eye) and, as the hours went by, I got to know my Queue crew: very nice people in front from Staffordshire, very nice people behind from Bedfordshire, and very nice people a bit further back from Ealing.

We chatted about our journeys and the weather; we talked about our families and our snacks; I pointed out my old high school and where I’d had my bar mitzvah party. Vicars shuttled up and down providing emergency succor. Stations gave out free tea and people shared biscuits. The mood was convivial in a very old-fashioned way, like some country fête had been stretched taffy-like into this slow-moving column.

But why … why were we there? I tried to get a grip on my slippery motivations.

In part, curiosity: Moments of social togetherness like this are rare historical comets, blazing into our social orbit only a few times a century … surely no-one could skip a moment so exceptional?

Or perhaps a desire to commune with some ancient national spirit … something deep and reassuring after Brexit and Covid? Maybe…

More unexpectedly: A fragile feeling of strange and shared loss. For the Queen herself, absolutely, who carefully and dutifully did an impossible job for 70 years. But also for some childlike certainty about the UK.

The Monarchy is now bound up with very necessary (and long overdue) conversations about centuries of injustice, but when I was in nursery—learning where I was from—the Queen was simply the person at the top … sitting on her throne, making sure we were all OK. As a child, she existed somewhere between Father Christmas and Robin Hood. And now she’s gone and some forgotten thread feels like it’s snapped.

In a small park nestled under the golden flank of Parliament lay the last and toughest part: three hours exhausted trudging in switchback queues. Here, zig-zagging back-and-forth dozens of times (as if for some funereal Space Mountain), Queuers began to focus on what was ahead of them. Conversation returned to the woman herself, who—over 12 hours—had been lost a little in chats about flapjacks and sore ankles.

My neighbors talked about real sadness and their wish to pay her this tribute. For many, the physical discomfort was a giving back—part-payment of a debt they’d decided they’d been building all their lives. “What’s a few hours standing,” said the very nice man a few in front, “when she gave us 70 years?”

People smoothed their hair and tucked in shirts; there was some discreet stretching. Then, after security (where we jettisoned food and water) everything suddenly moved very quickly. Rapidly ushered up the steps of the Palace, we passed into the extraordinary medieval space of Westminster Hall.

On entering the hall, there seemed to be an abrupt shift in the historical gravity. On the coffin, resting on the Queen’s standard, were the orb, scepter, and Imperial State Crown—all glittering with peculiar, antique light; uniformed guardsmen stared fixedly downwards at the corners of the catafalque; Beefeaters (usually jolly sorts in Tudor ruffs running tours at the Tower of London) were frozen into attitudes of utter grief.

It was almost entirely silent.

We had perhaps two minutes from entry to exit, and just a few seconds—enough to breathe in and out once—before the coffin itself. I nodded my head, then—with one quick glance back—was out the door. The psychic pressure dropped again.

Then I said goodbye to my Queue group (many in tears), and we parted forever.

The sun began to set and I began home.

When you’re still not entirely clear what your aims were, it’s hard to know whether you accomplished them … but I think I probably did, at least a bit. Certainly as I walked to the station, I felt indisputably lighter … even if I was unsure why.

But then when you’ve visited the fantastical realm of royalty—a place inhabited by lions and unicorns—a certain amount of mystery comes with the territory.

The Tube took me off into the Carolean age.