DP Books

The Marriage That Saved the Monarchy

The touching love story of King George VI and Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) and how they rescued the reputation of the British crown.

Prince Albert fell in love with Lady Elizabeth Bowes Lyon when they first danced at the Royal Air Force Ball in The Ritz hotel on July 8, 1920. She was vivacious and pretty, the “it girl” of her aristocratic set. She had already rebuffed proposals of marriage, some of them rash, some more serious. Albert joined the queue.

For more than two years, Albert courted Elizabeth. She turned down his marriage proposals twice, kindly offering instead to be “good friends.” It took the intervention of nearly a half dozen people to embolden him to try a third time.

The thought that he would one day become king never occurred to Elizabeth and certainly didn’t affect how she regarded Bertie [as Albert was known to family and friends] as a prospective husband. Whatever their personal chemistry, the best she could expect was life as a hardworking member of the royal family, dutifully carrying out countless public engagements that required strong legs and a constant smile.

After numerous maneuvers by friends and family members, including the timely removal of a rival to a job in America, Elizabeth accepted Bertie’s hand in January 1923. They were married four months later, to the immense pleasure of both families and their many friends, and she came to love him unreservedly.

Her mischievous and teasing manner was infectious. She loved to laugh, and her high spirits bubbled through her letters to family and friends, which she sprinkled with expressions like “tinkety tonk” and “what ho!” from P. G. Wodehouse, one of her favorite authors. “I write to the accompaniment of the squeaking of rats, melodious and soothing to a degree,” she told her brother Jock from St. Paul’s Walden Bury, “and the patter of their little feet in the walls calm my troubled brain—the little darlings. Bless them.”

Albert was as timid as Elizabeth was exuberant, as awkward and doubting as she was effortlessly confident, as formal as she was spontaneous and relaxed. Yet they turned out to be ideally matched. They both had what the British call “bottom”: integrity, honesty, and loyalty, bound up in an ingrained sense of duty.

Elizabeth’s gentle and encouraging manner helped soothe Albert’s temper and allay his frustrations. It was at her urging that he enlisted Lionel Logue, the Australian speech therapist who raised his self-esteem and tamed his stammer.

Albert and Elizabeth were—in different ways—more resilient and strong-minded than they appeared to be. When dealing with her husband’s adversaries, Elizabeth could be steely: “a marshmallow made on a welding machine,” in the words of photographer Cecil Beaton.

Toughness was essential in dealing with Albert’s bête noire, the pampered and careless Edward, Prince of Wales. The two brothers had enjoyed a reasonably congenial relationship growing up and had socialized during the fizzy 1920s. Elizabeth initially took pleasure in Edward’s company and wrote him breezy and affectionate letters. But his carousing and womanizing, and his deficiencies of character—selfishness, narcissism, duplicity, and disloyalty among them—pulled Albert and Elizabeth away from him.

The Prince of Wales knew how to turn on the charm and carry out his duties. Behind the smiles, he was bored and bitter about his fate, emotionally stunted and self-absorbed. In letters to his married lover Freda Dudley Ward he poured out his self-loathing and complained about his advisers and the people he met, not to mention those who entertained him. He expressed contempt for his family, especially his father, George V, whom he considered outdated and narrow-minded. At times he said he wished the monarchy would be overturned, calling himself a “bolshie.” Frequently depressed, he even spoke of suicide.

The public knew none of this, but over time Edward’s family and members of the court became aware of his flaws. Their biggest concern was his poor choice of women. While there were many flings, his main attraction was to married women: first Freda, then Thelma Furness, and, beginning in January 1933, Wallis Warfield Simpson.

Edward was obsessive and submissive with all three women—once writing to Freda that he was “the kind of man who needs a certain amount of cruelty”—but especially so with Wallis, whose dominance disturbed those who witnessed it. Once, when he was on all fours releasing the hem of her dress from the leg of a chair, she berated him mercilessly.

On December 28, 1935, King George V and Queen Mary invited some friends who lived on their Sandringham estate, Sir John and Lady Maffey and their daughter Penelope, to dinner. As they walked into the entrance hall, the Maffeys witnessed an altercation between the King and his eldest son, standing on the staircase as his father shouted from below: “You’ve got to get rid of that woman!”

Three weeks later, George V was dead, and the prince took the throne as King Edward VIII at age 41. He was a terrible monarch, inattentive and cavalier; his behavior and attitudes corroded the very center of the monarchy. He was determined to marry “that woman” once she had divorced her second husband.

During the complicated and painful abdication crisis of December 1936, Edward marginalized his brother Albert as well as his own advisers. When the British government rejected his effort to make Wallis his queen and he renounced the throne, Albert became the king, and he honored his late father by calling himself George VI. He was three days shy of his 41st birthday. The new queen, his wife Elizabeth, was 36. Edward VIII became the Duke of Windsor and Wallis his duchess.

The day of his accession, one of his cousins asked George VI what he was going to do. “I don’t know,” he replied. “But I am going to do my best.”

George VI and Elizabeth found their footing during the jittery prewar years between 1937 and 1939. They made triumphal visits to France, Canada, and the United States, winning hearts and minds everywhere. Over hot dogs at Franklin D. Roosevelt’s home in Hyde Park, the royal couple famously bonded with the president and first lady. Their mutual respect for one another’s character and temperament proved vital in the war years ahead.

When Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, George VI began keeping the diary that he would continue for more than seven years. The privilege of reading these pages in their entirety at the Royal Archives gave me an extraordinary lens on the momentous events of World War II and the leaders of the military and the coalition government. I could also appreciate in full the King’s intellect and common sense that were all too often underestimated. George VI’s daily jottings show his trusting and friendly relationship with Winston Churchill, his wartime prime minister. He understood Churchill’s overpowering personality and could detect his shifting moods. When the prime minister made a decision, the King observed, “personal feelings are nothing to him, though he has a very sentimental side.”

To an unusual degree, George VI shared his wartime responsibilities with Elizabeth. An “unprecedented” feature of the lunches Winston Churchill had with the King at Buckingham Palace each Tuesday “was the presence of the Queen at these private conversations,” according to Elizabeth’s official biographer, William Shawcross.

The King traveled more than 50,000 miles around Britain during the war, often straining his fragile constitution. The Queen accompanied him on most of these journeys in their heavily armored train and automobiles. They were constantly moving targets. Visiting bombed-out neighborhoods in London, they frequently defied air raid warnings. They spent nights on the train adjacent to tunnels where they could find protection if danger arose.

When they weren’t out inspecting military bases, factories, hospitals, ships, and damaged cities and towns, they risked their lives by spending their working days at Buckingham Palace. For three of the nine Palace bombings, they were present. In September 1940, government officials advised them to sleep at Windsor Castle, either in an underground shelter or in reinforced ground-floor bedrooms. There they endured regular air raid “Red Warnings” and heard the drone of enemy aircraft, the explosions of bombs landing nearby, and booming antiaircraft weapons.

George VI and Queen Elizabeth were effective during World War II not only because of their sympathy and thoughtfulness but also because of their innate feel for the soul of Britain. The King noted in his diary that “one of my main jobs in life” was “to help others when I can be useful to them.” That job took a terrible toll on his health, aggravated by his two-packs-a-day smoking habit and constant anxiety over making speeches.

The King and Queen found happiness in the marriage of their eldest daughter—their “Lilibet”—to Prince Philip, followed by the birth of their grandson, Prince Charles, and granddaughter, Princess Anne. They restored Royal Lodge, their war-damaged country house in Windsor, and they enjoyed meals in the gardens there when they needed to escape the formality of the castle. They entertained more, with dinner parties and dances for their friends. They had monthslong holidays at Sandringham and in the Scottish Highlands at the monarch’s Balmoral estate.

But their life couldn’t return to normal. During the last three years of his reign, George VI was frequently bedridden with cardiovascular disease and lung cancer. It was customary then for doctors to withhold a cancer diagnosis to spare the patient needless anxiety. Neither the King nor the Queen discussed the disease, even after his malignant left lung was removed. The doctors said the surgery was done to address “structural changes” in the lung.

George VI and Elizabeth took comfort in the illusion that he was getting stronger, even when his weakness was all too evident. Winston Churchill marveled that he had remained “cheerful and undaunted—stricken in body but quite undisturbed and even unaffected in spirit.”

Their 15 years as king and queen began with trepidation and uncertainty and ended with stoic suffering and premature death. They rescued and rebuilt a monarchy battered by the abdication crisis. In their wartime leadership, they showed the world their personal courage and capacity to inspire. And through example and instruction, they prepared their elder daughter for her eventual succession to the throne, setting the stage for a new Elizabethan age that would secure the foundation of the monarchy through the twentieth century and well into the twenty-first.

From the book George VI and Elizabeth: The Marriage That Saved the Monarchy by Sally Bedell Smith. Copyright © 2023 by Sally Bedell Smith. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

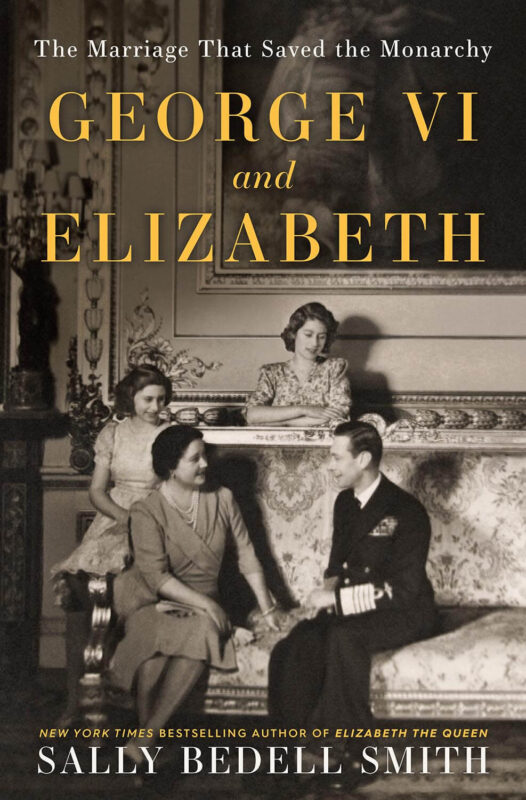

Hero image of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1948 by PA Images via Getty Images