From the Archives

Glorifying the Gigolo

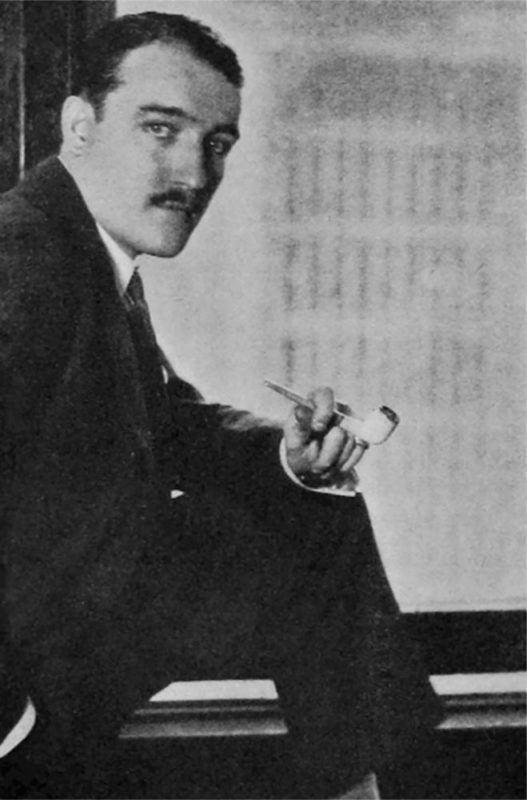

In the 1920s, Americans didn’t know what the term gigolo meant. The Marquis de La Falaise set out to change that.

Henri de La Falaise was many things—a nobleman, film producer and director, actor, and war hero also known for his marriages to actresses Gloria Swanson and Constance Bennett. But most of all, he was a master raconteur.

After three marriages, he died without children and the title passed to his younger brother Alain de la Falaise, who married Maxine Birley “Maxime” (sister to London’s Annabel’s nightclub founder Mark Birley whose son Robin Birley is set to open “Maxime” in New York this year).

In his only piece for Beau Magazine, published in 1927, the Marquis de La Falaise attempts to make an American audience understand what the term “Gigolo” really means.

Even in the distance exposed by the fashionable flow of Longchamps racing devotees, he stood out as an amazing and curious figure.

The women of our party stared at him admiringly—all women always did. He was undeniably handsome at the age of 30 odd, and was only just beginning to tend towards a very slight and debonair stoutness. But the men gaped at the splendor of his racing attire: his top hat, the purple carnation in the buttonhole of his tight-fitting, obviously London-cut away, his silver headed Malacca stick, and the pointed black patent leather shoes with their dove colored spats.

“Who is he?”

But I must tell you something about those charming voices, and about my little party of friends. The two girls, they were sisters. Barbara Winton, the elder one, says she is 29—I am not so sure about that, but I am quite sure that she was created and brought into the world to wear Monsieur Jean Patou’s gowns—and she did. A long, slim silhouette and blond hair. Two gorgeous eyes—lovely eyes—with lashes which certainly did not need the slight touch of mascara which she indulged in. No sense of humor. Through with life—love—everything; she would say so anyway without a smile.

Her late husband, so I heard, had treated her roughly during the three years their association had lasted, and had died suddenly after over-indulgence in varied and prohibited alcoholic beverages. He had left her the very large what remained of a yet-larger fortune, and since that eventful day, she always spoke of the late Mr. Winton with the respect and dignity becoming to a dutiful widow.

Her sister Claire had enormous greenish-grey eyes, a mouth like ripe cherries and naturally rosy cheeks. Full of pep. With all the sense of humor her sister lacked. She had come to Paris to have a good time and intended to have it.

“Who is he?” Claire repeated.

“A gigolo,” I answered, looking straight into the dilated pupils of her eyes.

“Do you mean that he is one of those horrible men who allow themselves to be supported by the fair sex?”

“Oh no,” I replied. “You Americans have the wrong idea of what the term ‘gigolo’ means. You call the dancing men you can hire in the cabarets of Montmartre ‘gigolos’, they are not gigolos because they are paid. No real gigolo is ever paid for his attentions. ‘Gigolo’ is the French slang word for ‘amant de coeur’—the heart lover. He is a man who is madly loved by the girl he loves (and when you have love Mesdames, money plays no part.)”

“Is that so,” Barbara interrupted.

“He is usually young and not rich enough to marry or to support a woman in style, but he always has enough money with which to entertain the lady of his heart. He takes her to teas, to dinners, to theatres, to dances; he sends her flowers, and just those little gifts which are so unimportant, but that a woman loves. He knows just when to be silent and when to speak—he is thoughtful, he is adored, he is priceless, and money means nothing to him—he is a true ‘gigolo’.”

“Oh tell us some more about that horrible man,” Claire whispered into my ear.

“Jacques de Lunac,” I began, “must have been born on a Friday, the day of Venus, the plump but luscious goddess. When ladies came to the house for tea, his mother would bring out little Jacques and the ladies would press him to their bosoms, feed him sugar plums and kiss him. And little Jacques never objected. His two brothers—slightly older than himself—would scowl in a corner and grimace at guests.”

When he fell in love with his governess at the age of ten, my aunt tells me he went to his neighborhood florist; he had no money, he just exerted a bit of charm and in a brief time wheedled a rose from the little widow who ran it. Child that he was, he knew even then that the way to the heart of your lady is through a flower—preferably a rose. He was a lazy little pupil, but the indulgent governess never reprimanded him.

Both of Jacques’ brothers found their vocations and settled into them without further ado, but Jacques displayed no talent, no particular appetite for anything except to love and be loved. And the ladies fell for him by the ton—which in these days means many.

All he had to do was be himself. He was most sensitive to every wish of his little courts and tried to realize the little wishes for them. But his chief charm lay in his languor. Women found his company very soothing. One matron, the wife of a perfumer manufacturer, tried to shower him with extravagant gifts, but he sent them all back.

There is a very distinct trait you know in women’s character, they like to give, they like to donate love—that’s the one thing you cannot buy from them. Maybe that’s why there are so many “gigolos” and why Juliette Pascall was estranged from her husband a few months after their marriage. In Jacques she found just what she needed, and she gave him enough love to intoxicate a man far more sophisticated than he was. They were happy—very happy. They transported their love from Paris to Venice and from Venice to the Fjords of Norway, via Biarritz and Deauville, and they always thought it would last for always.

And then the war came. Jacques was one of the first to enlist in the Flying Corps and for only one reason, he liked the pretty uniform. He certainly did look awfully well in it. Jacques came through the ordeal without a scratch. I can only ascribe his miraculous survival to the intervention of Lady Luck. The fickle goddess Glory took him under her protection, she made the friendly clouds envelop him when danger was imminent—envelop him like the draperies of his mistress’ negligee. And when the war was over Jacques’ uniform was covered with medals—“The Gigolo of Glory.”

And then came the most exciting period of his life. The ladies of Paris flocked to him, surrounded him to the point of suffocating the poor fellow, but Juliette however, was still the only object of his devotion.

But then he went and got married.

“Married? Why?” said Catherine.

“That’s just what the whole of Paris wanted to know at the time,” I returned. “It was his old aunt’s fault anyway. An old forgotten aunt of his insisted on dying on a fine April morning, and insisted on leaving all her money to Jacques, her favorite nephew.”

When Jacques got the news of this unexpected wealth, his first move was to get into a taxi and drive to Cartier. He then hurried to the home of his Dulcinea and without a word placed on her lovely arm the most gorgeous diamond bracelet that you have ever seen. And that’s where the trouble started.

Instead of thanking him in the proper fashion, she tore the bracelet off her arm and threw it to the floor.

“But why?” he demanded.

“Why—she wept—do you bring me such an expensive present. I don’t want your jewels. I don’t want presents from you—and what could I do with it? You know I can’t keep it, my husband would see it and then where would I be? You know how suspicious he is. The remainder was stifled in sobs.”

The “gigolo” looked at his weeping lover and then and there decided he would share her with no one. She would have to divorce and then he could marry her and he could give her all the bracelets he wished. After a week he finally succeeded in wheedling the final “yes” from her unwilling lips.

Paris did not wait long. A few months later we knew that his wife was, let us say, paying some attention to a young and not very wealthy but bewitching aviator, but it took Jacques over a year to discover it, and to find out that his rival was a stripling gigolo. And so Jacques the husband divorced and gave the money away to charitable institutions since it had brought him nothing but ill luck.

At this juncture, the hero of my story himself walked in and ordered a Tom Collins at the bar. Leaning leisurely over the railing, a perfect symphony in grey from head to foot but for the yellow strap holding his field glasses. He had a hat tilted in a debonair fashion. He swung around and facing us gave me a wink accompanied by a look meaning clearly, “who are these charming ladies?”

“May I introduce you?”

“Please.”

A few moments later the conversation had warmed up with the exception of Barbara whose attitude would have frozen a bottle of Worcestershire sauce.

They spoke of horses, music, modern, art, etc. Jules the barman was closing up. Finally, I succeeded in getting them all back to their hotel, much to Barbara’s relief.

I saw little of them until I bumped into Claire who said her sister was having a fit of seclusion.

Poor Claire, I decided to make her last few days less lonely and invited her on a trip to Cherbourg. Barbara refused to join.

On the trip after a few drinks, Claire’s voice startled me out of my thoughts. “By the way, you don’t know any more about that man at the races, that ‘gigolo’?” she said.

“No my sweet lady,” I answered. “I told you all I knew.”

At that moment I was interrupted by Paul, handing me a telegram. I took one glance at it. I could not believe my own eyes. After a silence I handed it to Claire with a smile. “There’s the end of that story,” I said.

And this is how the telegram read:

Henri here is the truth and please try to make Claire understand. I am utterly desperately in love with Jacques. He has entirely captured me in the last few weeks and now I find I cannot leave him. Thanks to the Gigolo as you called him. I now know what love means. – Barbara

Hero image: Été 1923, No. 53, illustration by Marc Luc, Wikipedia Commons.