The Great Migration

Westward Ho!

The top one percent have ditched fancy city townhouses for wide-open spaces. The American West will never be the same.

Back in late 2018, l left behind Brooklyn for Boulder, a small college town in the foothills of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains. Soon, the phrase “moisture-wicking” had entered my vocabulary and, witnessing my rustication, my friend joked that I should write a memoir: “From Prada to Prana: How I Ditched Heels for Hiking Boots and Fell in Love with the West.” When the pandemic and its lockdowns hit with full force in early 2020, I thought of friends trapped back in New York or London, unable to glimpse a scrap of green, and stopped making those kinds of jokes.

Then came the migration.

One of the most significant, pandemic-induced demographic reshufflings of the last two years has been the flight of the wealthy from East Coast cities like New York, Boston, and D.C. to places like Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana, and other neighboring states.

Once, these swathes of under-populated lands abutted what was disparagingly deemed “flyover country.” Now, private jets are landing there as increasing numbers of the financial elite choose to make their primary homes in the American West.

The great migration of recent years away from the East Coast (in 2020 alone, New York lost 406, 257 residents and, even though some have now returned, many remain merely part time) to these newly fashionable areas have called to mind a phrase from the modernist poet Wallace Stevens: “The westwardness of everything.”

By the end of 2020, it seemed as though every other car I saw on the roads in Boulder—once a modest, scruffy place with dreamcatchers dangling off every cornice and plenty of aging Grateful Dead fans mooching around in tie-dye—was a shiny new Tesla driven by a guy who looked like Ken from Succession.

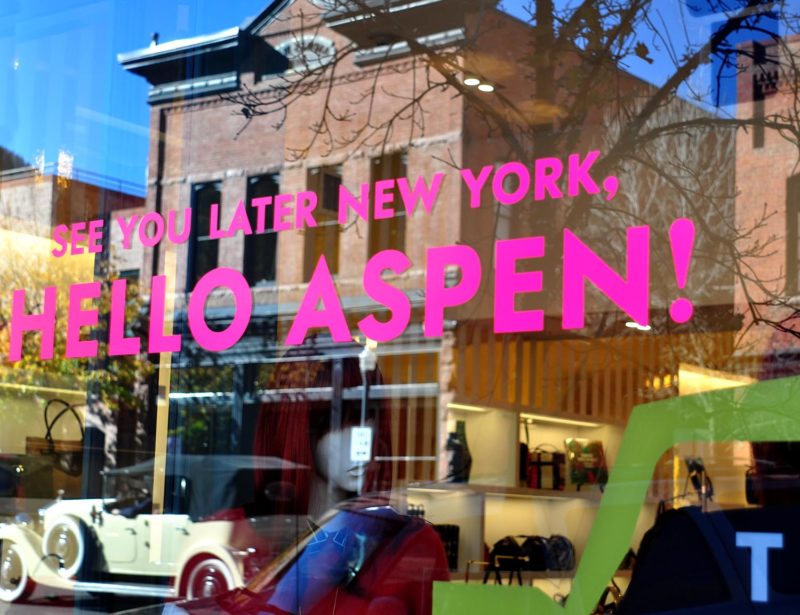

Boulder, however, remains decidedly downmarket compared to, say, Red Mountain in Aspen, where a nine-bedroom property recently sold for a record $72.5 million. On “Billionaire Mountain,” as the area is nicknamed, realtors are scrambling to come up with inventory for clients. And, as if further proof were needed of the turbo-charged gentrification of an already highly-moneyed area, Chanel recently opened a new store in town.

Wyoming is perhaps the most extraordinary example of the new western wealth influx. Now, the state’s top 1% of earners constitute half its income, making it the highest share in the U.S. The average annual income for Wyoming’s top .01% is an extraordinary $369 million, compared to around $70 million for New York.

It’s not just the wide open space, but the significant tax breaks that have lured the one percent to the state. As one resident of Teton County told the Financial Times, it represents “the best onshore version of an offshore trust.”

Teton County is also the subject of Yale sociologist Justin Farrell’s book, Billionaire Wilderness: The Ultra-Wealthy and the Remaking of the American West. Published by Princeton University Press in 2020, the book charts the deeply uncomfortable phenomenon of billionaires chasing the mere millionaires out of town, all while socioeconomic inequality worsens.

One particularly damning detail depicts the hypocrisy of an oil baron whose $35 million ranch stands heated and vacant for most of the year yet, when he flies in on his private jet, he instructs staff to print on both sides of a sheet of paper for environmental reasons. Farrell, himself a Wyoming resident, also describes the ways in which the ultra-wealthy purchase land and then place their properties under “easement,” which not only prevents future development but, crucially, grants them tax relief.

Putatively conservationist gestures like this are one way for new arrivals to broadcast their munificence. Wilderness or not, the rich and powerful will always find new ways of tooting their own horns. One such medium for this is Strava, the app that tracks a user’s exercise data—in other words, how far and how fast they hiked, ran, or biked. Braggadocious billionaires new to the West and training for triathlons might strive to attain “King of the Mountain” status, in other words, to be crowned the top performer on a given segment of trail.

Nature, as the kids like to say, is healing. But it turns out that not even the sobering magnificence of the Rockies can mute the egos of the competitive and status-conscious. And nothing says status more than a sprawling ranch. The more remote and the fewer connections with other people the better.

Designer Tom Ford’s 20,662-acre Cerro Pelon Ranch near Galisteo, New Mexico, which had been on the market for years, famously sold last winter to a family with homes on both coasts. While the purchase price was not made public, according to the Santa Fe Association of Realtors, it’s believed to be the highest property sale to date in the county. (Ford had previously cut the asking price from $75 million to $48 million in 2019.)

Alex Maher, president and co-founder of the luxury real-estate firm Live Water Properties that specializes in ranch sales across the Rockies, confirms that soon after the pandemic hit, demand soared and sales boomed. Last year, land sales in Montana increased by more than 50% and transactions exceeding $10 million were at historic levels.

2021 also saw the biggest dollar amount ever paid for a Montana ranch when Climbing Arrow, an estate of almost 80,000 acres, sold for $136.25 million. The figure makes the $45 million that Michael Bloomberg spent in 2020 on his 4,600-acre Colorado property in Rio Blanco county (a ranch complete with golf course and helipad) look almost modest in comparison.

“We’ve run through the inventory in the past few years,” says Maher. “There are more buyers than sellers.” Those looking to acquire these kinds of large, rural properties, he says, are typically, “50- to 70-year-old folks who’ve sold businesses or accumulated wealth one way or another and have enjoyed time in the West on vacations in an existing resort home or ski condo.” Many, he admits, “don’t have experience of owning or operating ranches that have livestock or agricultural operations, but they’ve traveled the West at some level, whether summer fishing trips, winter skiing trips, or family holidays at dude ranches.”

One of region’s less-than-experienced ranchers might include one Mr. West, who famously bought (and then, following his divorce from Kim Kardashian, listed for $11 million) a property outside the small town of Cody, Wyoming. The rapper’s “Follow God” music video from 2019 delivered us Kanye in Carhartt overalls and sturdy gloves, roaming around the snow-bound fields of Monster Lake Ranch with his dad. Elsewhere in his adopted state, particularly in wealthy Teton County, his fellow billionaire arrivistes were ditching bespoke Italian suits for Wrangler jeans and cowboy fantasies.

Liz Stanley, founder of SayYes.com and The Huddle, who left San Francisco 18 months ago with her family and decamped to Montana, says she understands the frustration with the new money and people rolling into what some are now calling ‘The B-Circuit’—Bend, Oregon; Boise, Idaho; Boulder, Colorado; and Bozeman, Montana. The latter has experienced an 82% increase in airport passengers over the past five years, with over 1.94 million travelers in 2021 alone—a number that equates to almost twice the population of the state.

Besides the influx of activity, Stanley says that for locals, “Affordable housing is a big concern, community health resources are a big concern, and as this Yellowstone Valley is the American Serengeti; wildlife habitat, land use and conservation are big concerns too.”

Much of the push back Stanley sees against ‘city people,’ comes from residents worrying that the former are bringing the city with them and not respecting or understanding the way of life they hold dear. “Right now I’m still trying to wrap my head around it all,” she says, adding, “People aren’t looking to fight, they’re looking to find ways to connect.”

It’s an admirable sentiment, which (alas) also happens to be rarer than we’d all like. In February of this year, the long-running, adult-cartoon South Park ran an episode titled “City People” which gleefully and violently skewered the rural real-estate boom.

When the episode’s fictional, titular small Colorado town is flocked with urbanites, we see them pecking around, pigeon-like, while blurting a limited script of yuppie phrases: “oat milk”; “cortado”; “Tesla”; “Pilates.” It turns out the town’s real enemies, however, are the real-estate agents—venal, maniacal and, ultimately, hoisted on their own petards.

Hero image: Teton County, Grand Teton National Park; Photo by: Dukas/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.