Equestrian News

Ocala’s Trifecta: Land, Love, and God

What are the odds that a Disney-style Equestrian Center will give Wellington a run for its money?

The miraculous interior pocket of lakes and rolling hills surrounding the ruggedly historic city of Ocala doesn’t much look like the Florida of popular imagination. Replace the beaches and (most of) the palm trees with red maple, dogwood, magnolia, and pine trees. Drape Spanish moss for a heavy dose of depth and atmosphere. Then, add sparkling crystal lakes and honest-to-goodness hills rolling out gracefully in every direction.

Horse farms and shows have been part of this Central Florida hamlet’s culture and economy since World War II. In recent decades, the bucolic region 37 miles south of Gainesville has even come to vie with Lexington, Kentucky for the title of “Horse Capital of The World.” In its 1999 census, the USDA put the number of horses here and in surrounding Marion County at 35,000; by 2018, that number had more than doubled, to 80,000.

But while Marion County’s horse population was exploding, the area still remained relatively unknown. That is, until the Roberts family broke ground in October 2017 on what would become the grandly-named World Equestrian Center – Ocala (WEC—pronounced “weck”—for short), a state-of-the-art facility that aims to put Ocala firmly into the equestrian circuit and vie for the “Horse Capital” crown.

A Best in Breed Facility

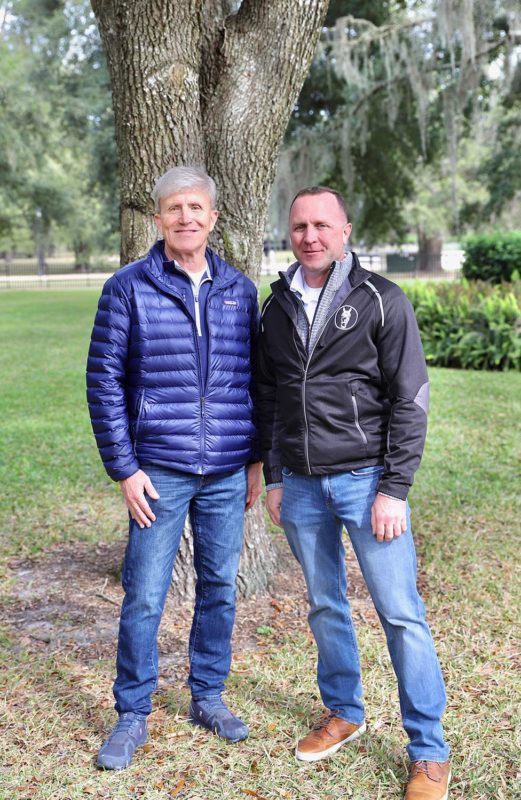

Fast forward to January 2022 and Vinnie Card, WEC’s soft-spoken Director of Operations with a sly smile, recalls asserting Marion County’s claim to the “Horse Capital” title straight to the face of a recent Kentucky governor no less.

Vinnie’s a bit sheepish about the exchange, chalking it up to a mix of fun and respectful rivalry. But given he’s making his point while standing in WEC’s 132,000-square-foot Exposition Center, one of dozens of new buildings that occupy what’s now the largest equestrian complex in the United States, it’s hard to imagine he didn’t entirely mean it.

WEC’s bustling, 378-acre mega city 10 miles west of downtown Ocala can be difficult to comprehend, even after a residency of several days. The newly tamed landscape-within-a-landscape here contains 1.5-million square feet of riding space and supporting infrastructure.

Equestrians can enjoy over 250,000 square feet of outdoor event space, including an imposing stadium and jewel-in-the-crown Grand Outdoor Arena; five indoor riding and show venues totaling a shade under 350,000 square feet; a “Jumper Village,” with two outdoor venues; and a whopping 3,000 padded and climate-controlled stalls. Vinnie traverses the place from before dawn until dinnertime in a vehicle that marries a golf cart with a Humvee.

Rumored to have cost $800 million to build, every single aspect is a knockout. Arenas are outfitted with GGT-Footing, the most-advanced arena footing blend available today. Facilities are gleaming and air-conditioned. There are overhead fans in the stalls courtesy of the Big Ass Fan Company. There’s even an RV park, gas station, and convenience store at WEC’s periphery for added comfort and support staff.

The 248-room, mansard-roofed Equestrian Hotel presides over the Grand Arena at the epicenter of the sprawling new development. Brilliantly white, it nods to England and even more heavily to France. The Yellow Pony pub off the soaring lobby bustles with jodhpur-clad guests; the Stirrups restaurant delivers a grand dining experience; and Emma’s Patisserie drops a bit of Paris into the mix, serving “authentic macarons” with Starbucks coffee.

The overall vibe is distinctly American: Despite its grand scale, it’s warm and approachable, a casual luxury consumer’s dream. At midweek in January, there’s an easy calm to the scene. By Saturday, it’s jumping with a swirl of visitors from near and far. Horse people from all disciplines mix with each other—often, by virtue of WEC’s unique ability to host hunter/jumper and dressage shows on the same weekend, for the very first time—and with curious locals.

WEC is already, in its very first year, quite a spirited party. It’s all an exquisite formula, really—an end and a means: The affluent and glamorous pay handsomely to be at the center of the action. And they, in turn, are the draw for successive rings of onlookers and aspirants, who also become paying customers.

As WEC has become the new center of gravity for Marion County seemingly overnight, its pull is also being felt further afield. Attention, gossip, and curiosity have broken out at Wellington, Florida’s pedigreed horse mecca just inland from Palm Beach, four hours to the southeast.

Suddenly, the internationally acclaimed host of the Winter Equestrian Festival—the premier hunter/jumper and dressage showcase of the Palm Beach season—has to contend with a new facility with capabilities to match, and even exceed, anything anywhere else. Could Wellington’s equestrian reign actually be challenged from up the Florida Turnpike?

While interest in the new project is high, it’s also tinged with skepticism. “WEC is designed to hold world-class events,” declares an insider with longstanding business and riding interests at Wellington who has spent time at WEC since its January 6, 2021 grand opening. “And it’s top-notch. It is. The venues are fabulous.”

But, the Wellington veteran cautioned, WEC’s advances in horse care and comfort could only go so far. Palm Beach’s social cachet and wealthy denizens—the thoroughbreds atop the horses who dictate both horse market and real-estate prices—will keep Wellington in its own stratum. “It’s just a different mentality.”

Placing Bets on the Roberts Family

Visionary developers Ralph “Larry” Roberts, his wife Mary, and their children have been escaping Ohio winters for Ocala for decades. As Larry turned a single moving truck into R+L Carriers, a national moving and shipping empire with a 21,000-strong fleet, he began buying horses, starting with a broodmare. The animals became a guiding part of his family’s life. “You can’t let go of horses,” Mary explains. “They’re your babies.”

The surging growth of R+L, combined with the clan’s love affair with Ocala, naturally led to real-estate ventures. The Roberts’ first land acquisitions were for personal uses. Then, Reagan-era ambition begat the Golden Ocala Golf and Equestrian Club, featuring exact replicas of storied holes at Augusta and St Andrews. The place thrived thanks to the Roberts’ knack for delivering prestige in a convenient and digestible package. (The Roberts’ first club will soon undergo renovations at the hands of Ric Owens, Mary’s all-purpose design guru, to elevate it to WEC’s more bedazzled standards.)

“When we built this facility, we had the horse in mind at every stage,” is WEC’s official stance. “From the footing, to the rings, to the stabling, as well as our policies around horse welfare and anti-doping. WEC Ocala was conceived with the welfare of the horse as a guiding priority.”

Delivering on that mission comes down, in large part, to Roby Roberts, WEC’s second-generation leader. If horses are his mother’s babies, caring for them, and the people who love them, is Roby’s lodestar. His quiet-but-firm influence over every aspect of the creation and staffing of WEC has helped instill a culture of capital-C ‘Care’ and capital-S ‘Service’. Not just the hospitality kind, either; the spiritual kind, too.

Spiritual Dressage

WEC’s underlying spirituality reverberates across the property: Bronze crosses dot the landscape and a stone chapel is tucked into a grove of oak trees near the venue’s so-called Hunter Land.

Capped with a modest steeple, the chapel has a broadly “Early American Revival” look: Picture a little bit of New England, cut with some Pennsylvania, and maybe dusted with Norman Rockwell–esque innocence and nostalgia. It’s an ode to Main Street American Protestantism in a Megachurch age, but with the added dazzle of ornate moldings and twin rows of chandeliers running the length of the nave, one for each side of the congregation.

In late afternoon, the locally-made stained-glass windows—studded, at Mary’s request, with Swarovski-crystals to match the chandeliers—bespeckle the chapel’s interior with multicolored flecks of light, creating an unanticipated rainbow effect that now draws crowds daily. Bibles and pocket-sized wooden crosses are also set out, free for the taking, as a gift to all, courtesy of—or a blessing from—the Roberts family.

“God did good,” Mary is fond of saying in response to praise for her family’s work as she goes about her business at WEC. She likes to slip in through the side entrance of the Equestrian Hotel to watch two of her most-cherished pet projects, Emma’s and the Mr. Pickles & Sailor Bear Toy Shoppe, hum with activity. She imagines her grandchildren gathering at WEC “75 years from now,” to remember their early lives entwined with the center’s development.

Amanda Steege is certainly a believer in what’s happening at Ocala. Born into a deep New England riding tradition, the owner of New Jersey’s Ashmeadow show barn remains a highly competitive equestrienne herself. Last year, she placed first in the World Champion Hunter Rider at the Wetherill Palm Beach Winter Spectacular; this January, she took the top prize at WEC’s first Friday Hunter Derby of the Ocala Winter Spectacular.

While Amanda has attachments to many shows and venues, she’s now an Ocala resident and a fixture on the scene. “I love showing,” she says. “I love horses. And this is also what I do; it’s work. But this place makes it exciting.”

Amanda lauds being able to quickly refresh at the Equestrian Hotel’s spa after a day of riding, before attending a birthday party. It’s a pleasant leap forward in local horse-show civility. Ditto the militarily-precise WEC operation that gets manure from stables to covered bins and then carted away before the usual smells and flies even arrive.

Above all, though, she credits the horses’ padded and climate-controlled comfort as a critical difference. “I was worried about it being somehow clinical, but that was entirely wrong,” Amanda says. “I find the horses are almost always calm and quiet. They just sleep really well here. And that makes me happy.”

Jockeying for Position

The comforts of WEC have not gone unnoticed down in Palm Beach. The centralization of all aspects of horse show presentation and hospitality, plus the attendant revenue streams the Roberts have modeled, appear to have caught the attention of the Global Equestrian Group. The Denmark-based outfit moved last summer to acquire Wellington’s venerable Palm Beach Equestrian Center, home to the Winter Equestrian Festival, with plans to invest in “equestrian lifestyle initiatives” in partnership with the center’s previous owners.

Meanwhile, the United States Equestrian Federation has also agreed to hold USEF-sanctioned events, including prestigious hunter/jumper shows, at WEC starting this June.

While the dates still obviously defer to Wellington’s—whose well-heeled set will have already departed Florida’s summer humidity for the cooler climes by then—USEF recognition is nonetheless a critical step to achieving WEC’s larger vision of promoting Central Florida as a year-round riding destination. One that caters perhaps to a new breed of Florida rider, one who doesn’t trace his or her lineage back to Europe, and who is less-drawn to the traditionally-celebrated equestrian events of hunter/jumper and dressage.

The flags flying over WEC’s Grand Arena at the Coors Light Grand Prix this past January certainly tip to a new rider ethos: In lieu of the French, German, and British flags common to heritage shows like Wellington’s, banners for the United States Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard fluttered instead. And, despite the unusual chill in the air, the $5,000-a-pop tables on the Equestrian Hotel’s wide terrace were full of happy, well-fed folks admiring the magnificent horses and riders circling the course.

At the end of the event, Vinnie, eternally on the move to ensure that every last aspect of the scene works as it should, began to settle into momentary satisfaction. WEC is everything to Vinnie—he’s dedicating his life to it. “I learned a lot,” in earlier jobs around horses and shows,” he says. “But it was here that it really all came together.” Here, with the Roberts family, there was some fundamental meaning to all they had built—and continue to build.

The construction, the dining, the socializing, the sponsorships, and the croissant-laden tourists keep Ocala humming. The road into the complex is already being widened from two lanes to four; a second, 400-room hotel is going up at WEC’s periphery; and the surrounding land is being carved up for WEC-affiliated residential development. “I don’t know…when I see a kid on a horse for the first time…or a family together, that’s all I really need,” Vinnie says. “That’s what it’s about. It’s a good buzz.”