Activism

Ladies Who Don’t Lunch

These New Yorkers are fed up and want to kick restaurant sheds to the curb.

Ina Lee Selden is livid. She’s bundled up in a pink wool hat and a long down coat on a cold November day, so it’s a bit hard to see just how angry she is—but she is happy to tell you. “None of them pay anything. They don’t pay any taxes, they don’t pay any rent to the city, and no one’s minding the store!”

What’s got Selden riled up are the restaurant sheds littering the boulevards and side streets of New York City. Here on Ninth Avenue in the rump end of Hell’s Kitchen, a few blocks from her home, the sheds stick out into the parking lane, extend sometimes tens of feet past a restaurant’s store front, climb on to the sidewalk, and often leave less than four feet for pedestrians to get by (the law requires eight).

Cheri Leon, a TV production designer, reached her limit in the early months of the Covid epidemic, when she was working from her walkup studio in SoHo and the night-time noise from the restaurants around Father Fagan Square at Sixth Avenue and Prince Street was driving her nuts. “I was trapped in my apartment, working 60-hour weeks, with all that craziness under my window,” she said recently.

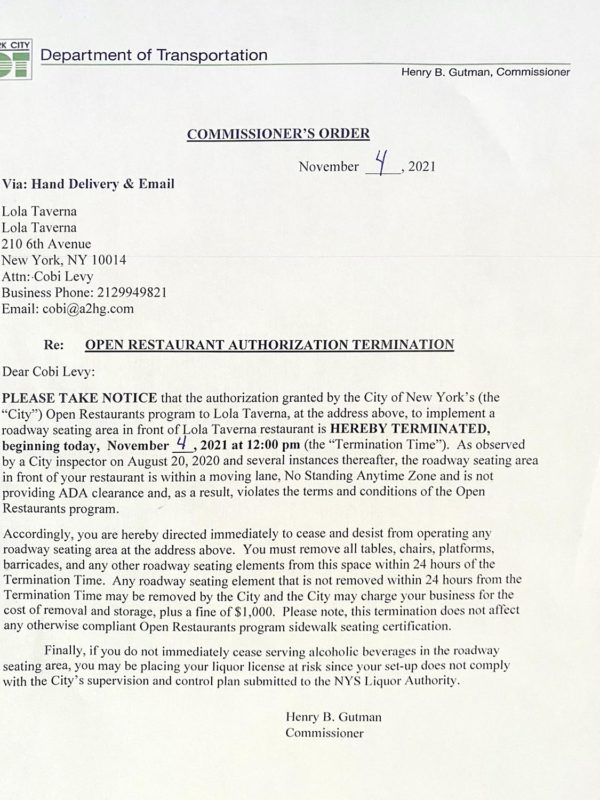

Ms. Leon saw an article on a local news site and realized there were kindred souls in her neighborhood who were equally furious, holding weekly gripe sessions about local eateries like Lola Taverna. Its double-row of tables on the sidewalk and another double row in a shed in a traffic lane brought garbage, vermin, and, tragically, junkies and homeless people, who took to using the sheds for a quick snooze.

For Shannon Phipps, a founder of the Berry Street Alliance in the heart of Williamsburg, the epiphany came when she tried to pass by a restaurant on Bedford Street with tables on the sidewalk, a street shed, and, as she recalls, a five-foot-high A-shaped signboard. She and her stroller-bound one-year old were shoved into the sign on the narrow sidewalk. She complained to the waiters. “They looked at me like I had no right to be a mother in this neighborhood and no right to be on the sidewalk.”

In Brooklyn’s less-trendy precincts, Robert Comacho, the chair of Community Board 4 and a long-time tenants rights activist, said the late-night noise pushed him over the edge. “It’s 11 o’clock,” he says, addressing an imaginary audience of al-fresco dining millennials. “Go inside, everybody’s gotta get to work.”

Over the space of a few months in the summer of 2020, Selden, Leon, Phipps, Camacho, and a half-dozen others, helped to form a group called New Yorkers for Safe Open Streets, which became CUEUP the next year (the acronym stands for Coalition United for Equitable Urban Policy). What unites them is a visceral hatred—shared, it would seem by a growing number of New Yorkers—for the temporary plywood sheds, the noise and the rats they bring, and the rampant restaurant colonization of the city’s roads.

“It’s a giant contradiction,” says Phipps, the Brooklyn stroller-mom, of the dining industry’s need for sheds. “They say you can’t eat inside the restaurant because you will die from Covid, but we can build indoor sheds outside and magically Covid will skip that. I still can’t understand the logic of that.”

Working with a former civil rights lawyer, Michael Sussman, the CUEUP folks have filed a pair of lawsuits in state court, seeking to have the current program halted. They argue that the city never held a proper environmental review (a state appellate court said their suit wasn’t yet ripe), and that the emergency order that established the Open Restaurants program should be replaced by a new law with public hearings, since nearly every other pandemic restriction has been ended. (That suit is still pending).

What they want is a process to give locals a voice in where sheds go, and end what they see as a giveaway of public space to the restaurant industry, landlords and paying customers.

“We want to be part of the conversation, and we are not part of the conversation,” says Leslie Clark, another CUEUP founder and a leader of the West Village Residents Association. “Our neighborhoods have been transformed—I lived in an area that had more outdoor dining than four boroughs combined, it was well-regulated, it followed rules that respected the residents, there was nothing wrong with it. What we have now is a free for all—it’s not just a lack of enforcement, it’s that the rules themselves don’t respect the residents even if they were to follow the so-called rules.”

Before Mayor Bill de Blasio signed the Open Restaurants decree in June 2020, sidewalk dining was regulated by the Department of Consumer Affairs. Permits took restaurant owners on a lengthy route through local community boards and several city departments, which evaluated their impact on neighborhood noise, crowding, and sanitation, and required a fee of as much as $30,000 a year. Now, the sheds are free, the application process is a single page, and the City shows no signs of reining in the program. In fact, Mayor Eric Adams says he wants to make the program permanent.

The CUEUP folks also want to get rid of the rats that nest under the increasingly dilapidated structures, and the outdoor free-for-all that has robbed their neighborhoods of their previously relatively pleasant quality of life. Phipps says her neighborhood is being stolen from her. “There are rats everywhere, it’s loud, it’s dirty, it smells like rat poop.”

“The question is who should be allowed to commercialize the public realm,” says Leon. “Is this really for the people? It seems it’s really for the paying customers.” They blame the city’s restaurant trade association, the New York Hospitality Alliance and its chief, Andrew Rigie, who convinced City Hall that restaurants would die without free space, and they accuse him of of working with the bicycle-riding anti-car group Transportation Alternatives to close streets to cars and fill them with rat-infested dining sheds.

Without a set of rules, the CUEUP people argue, the sheds will stay. As Shake Shack founder Danny Meyer recently told New York Magazine, why pack up his shed? “The city’s not charging rent to be there, and I don’t have a place to put them. So unless you give me a disincentive to keep it up, I’m just going to keep them up.”

CUEUP leaders contend that the City has judged the Covid crisis to be over (they note that schools and subways no longer require masking), but still the restaurant industry feels, as Clark puts it, “that they are a special case and deserve the free use of public space for two-and-a-half years.”

Free space isn’t the only give-away that the restaurants are getting. New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli noted in a report earlier this year that $2.8 billion in federal Covid relief funds had flowed to restaurants in New York City (the vast majority of it to eateries in upscale zip codes). In Manhattan, restaurants not in lower- and moderate-income communities received about 94 percent of the borough’s aid, at an average of $855,000 per restaurant.

Daniel L. Doctoroff, Mike Bloomberg’s former right-hand man—who tried, disastrously, to bring the Olympics and a massive football stadium to Midtown West, and has since restyled himself as an urban solutions guru with Google-owned Sidewalk Labs—cautioned against letting the dining sheds put down roots. In a New York Times op-ed last summer he warned: “Before it is too late, we need to take these temporary structures down. In their place, we should install a more flexible system that could meet our city’s changing needs—whether that’s upgraded dining sheds, freight zones, community gathering spaces or more we haven’t even dreamed up yet.”

On a recent Wednesday lunch hour, several dozen CUEUP members gathered in front of the City Council’s offices near City Hall. They came concerned that a closed session of the Council was set to approve a bill making the sheds permanent, and handing enforcement to the Department of Transportation, a notably hidebound agency that since the pandemic sheds first rose, has shut down only a few dozen of the 12,000 or so across the city. The Department has about a dozen inspectors to cover all five boroughs.

“This is the one thing that is most complained about, it affects everyone,” said freshman City Council Member Christopher Marte, who represents Lower Manhattan. Marte says he, too, wants to see a reasonable solution that’s more than a giveaway to the restaurant industry. He wants rules that make for safer and cleaner structures, give Community Boards and local residents a say over licensing, and enforce the hours that dining sheds can stay open.

“The wrong thing is one-size-fits-all,” Marte says, before turning to the crowd and promising to push his fellow Council members to hold hearings. (The proposed closed hearing was canceled that morning).

“We’re gonna continue to be here until we get the piece of legislation that chucks the sheds and gives us our neighborhood back,” Marte shouts to the mostly middle-aged, middle-class white folk carrying signs that read “Public Hearings Now,” and “No Closed Room Deals,” or more succinctly, “NYC to Residents: STFU.” The crowd responds with wild cheers, chanting “Shut the shed!”

Strolling around the protest with a megaphone, Camacho takes a brief respite from riling up the crowd. “This isn’t Puerto Rico, with big wide streets,” he says to a reporter with a hint of his native Mayaguez coming through in his NuYorican accent. “It’s not Paris,” chimes in a well-dressed, middle-aged woman with white hair. “Puerto Rico,” responds Camacho, before resuming his tirade against what he sees as just one more example of City Hall and the upper crust—in this case the restaurant industry—running roughshod over those with less money and less access to power. “Give us a process,” he says. “Do not do the Christopher Columbus syndrome of I do what I want and throw the natives out.”

On November 18, Mayor Adams held a press conference declaring his intent to sign legislation fighting the upsurge of rats on New York City Streets: “I have made it clear, I hate rats,” he said. “And we are going to kill some rats.” The solution, he said, is less garbage on the streets, better containers to hold the garbage. He made no mention of restaurant sheds.