Apartment Living

Holy Smoke!

The Devil’s Lettuce has come to Park Avenue. More pungent than cigarettes, pot smoke is now the subject of co-op board meetings. But what can really be done about it?

It’s everywhere, all the time. Since marijuana was legalized in New York State a year ago last March, thousands of revelers have been lighting up outside. Walking down the streets. Sitting on stoops. Bus benches. Community gardens. Parks. It’s a miracle the rest of us aren’t getting contact highs from the heady wafts as we go about our daily life in our beloved city.

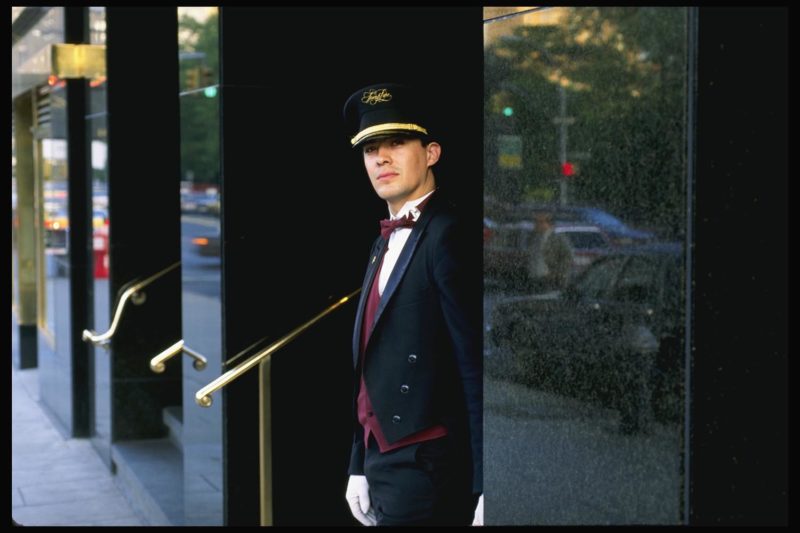

But has pot smoke snuck past white-gloved doormen and infiltrated the storied co-ops of Fifth and Park Avenue? “In a word, yes,” says Anthony Milstein, Vice President and Managing Director of Brown Harris Stevens Residential Management LLC.

While New York City requires all multi-family dwellings (aka “rental buildings”) to establish a smoking policy, it’s a bit more of the Wild West for co-ops.

“Unless a co-op has a provision in its proprietary lease prohibiting smoking in the apartment, it is technically okay to do so,” notes New York real estate attorney Robert Braverman, a managing partner of Braverman Greenspun. (And good luck if you want to lobby your fellow shareholders to ban pot smoke in your building; under the law, all forms of smoke are considered equal, so any amendment to your proprietary lease would have to outlaw cigarette and cigar smoking too, even in your own apartment. Not every co-op is willing to pursue such draconian measures.)

“Marijuana has a more pungent odor than tobacco, and there is certainly a novelty to it, and it’s going to bother people who are sensitive and who have little kids,” Braverman adds.

No kidding.

Diana, a mother of two middle schoolers, lives in a full-floor, fancy Park Avenue co-op but despite her tony address has been battling pot smoke odor in her apartment since the day a thirtysomething downstairs neighbor moved in. From the get-go, he toked “every day, twenty-four seven, my daughter’s nursery reeked of pot smoke,” laments Diana, who requested we use a pseudonym. (In fact, every shareholder, tenant, and board member interviewed for this story spoke only on the condition of anonymity, such is the fear of stirring the pot. Pun intended.)

Diana tried quite a few avenues to get help. First she enlisted her doorman—her building’s de facto peacekeeper—who confronted the new shareholder only to be met with the guy’s blithe denial. Next, she called 311. A bored-sounding city worker told her to file paperwork that, no surprise, disappeared into the ether.

Diana tried the police. They laughed at her.

After legalization, the problem worsened as the neighbor grew bolder, throwing pot parties at all hours, the stench now filling her entire apartment. Desperate for relief, she appealed to her co-op’s managing agent who told her to buckle up, “Smoking is allowed in the building and it is legal.” She finally lodged a formal complaint with her co-op board, which did discuss the tenant’s lifestyle during multiple meetings, but could not decide on a proper course of action. With the powers that be shrugging at such complaints, what can a sensitive New York City dweller do?

Braverman has long-awaited good news for co-op owners who have resisted the lure of sexy new condo development. “Even if you have an old-line Park Avenue or Fifth Avenue co-op board that hasn’t amended their proprietary lease in 40 or 50 years,” says Braverman (my co-op, for instance, still prohibits velocipedes in the public halls), “there are still lease provisions that prohibit transmission of foul odors.” So, “if your apartment is a virtual smoke stack there are remedies for the co-op to pursue including lease termination if the tenant shareholder is in breach of the lease terms.”

A co-op board has much more ammunition than a condo to take action. Since condos are owned outright by purchasers, there are typically minimal “house” rules, and those pertain only to common areas. But a co-op is actually a Corporation that owns the building, including the shareholder’s apartment. A shareholder essentially buys the right to “lease” their apartment from the Corporation, and is governed by a landlord (the Corporation) tenant (the shareholder) lease. Braverman explains, “if you default under the terms and obligations of that lease, the co-op can terminate it.”

How does that work?

“As a landlord, the co-op has a statutory ‘warranty of habitability.’ If someone is getting smoked out of their apartment and the co-op board does not take ‘reasonable steps’ [to mitigate such disturbances] the shareholder would be entitled to an abatement of their maintenance, theoretically,” Braverman continues.

Unfortunately, in reality, evicting a tenant shareholder from a co-op is extremely difficult, almost impossible. The Corporation would have to embark on Pullman proceeding (which dates from the case 40 West 67th Street versus Pullman). Litigation can cost a building tens of thousands of dollars and can take years. Worse, co-ops are often unsuccessful in these lawsuits, and the victorious shareholder can come home from court and light up.

All of those monthly assessments and no results? “It’s high stakes poker,” Braverman acknowledges.

No wonder Diana’s co-op board president recommended “writing the neighbor a nice note.” Sure, she’ll pull out the Tiffany stationery right now.

The City of New York, which has no jurisdiction in the governance of co-ops, recommends resolving these issues person to person. A fact sheet regarding secondhand smoke, found on the city’s Health Department’s website profers: “If you do speak with your neighbor, use a friendly approach. Tell them the smoke is entering your apartment and affecting you or your family’s health.” It goes on to provide resources for mediation like the New York Peace Institute which can assign a mediator to help consumers deal with these NIMBY issues.

Samuel, president of his Fifth Avenue co-op for years, described a recent issue with a teenager smoking pot in the back hall. “Of course we knew who it was. The doormen know everything, which parents are out of town and which kids are home. The super visited the family personally and the problem stopped.” I asked Samuel if these events were discussed at the board meeting. He said yes. But when asked if this made it into the board minutes, he replied, “minutes are selective.”

Not all New Yorkers who have pot smoking neighbors find it disturbing. As Malcolm, a twentysomething Brooklynite puts it, “Pot smoke is a part of life. If it bothers you, then you don’t know what’s going on in the modern world.”

But respite from “the modern world” is one of the most desirable aspects of these elegant buildings.

The moral of the story? Love thy pot smoking neighbor.

Photo credits from top: 740 Park Avenue, HONDA/AFP via Getty Images; marijuana leaf, Oren neu dag, CC BY-SA 3.0; Doorman, Lawrence Manning via Getty Images; woman trying vape pen, Ben Gabbe via Getty Images for Kurvana; dinner party, Ben Gabbe viaGetty Images for Kurvana.