Then & Now

Have we learned nothing from 1720?

Oops!...We did it again.

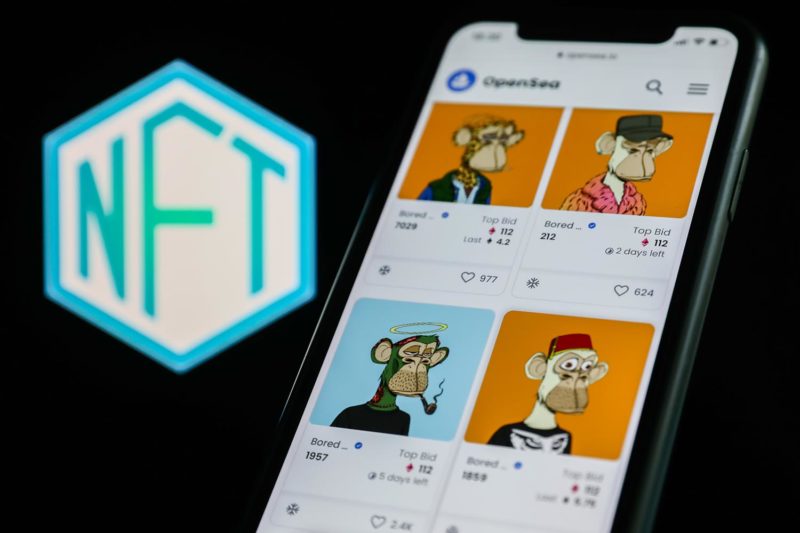

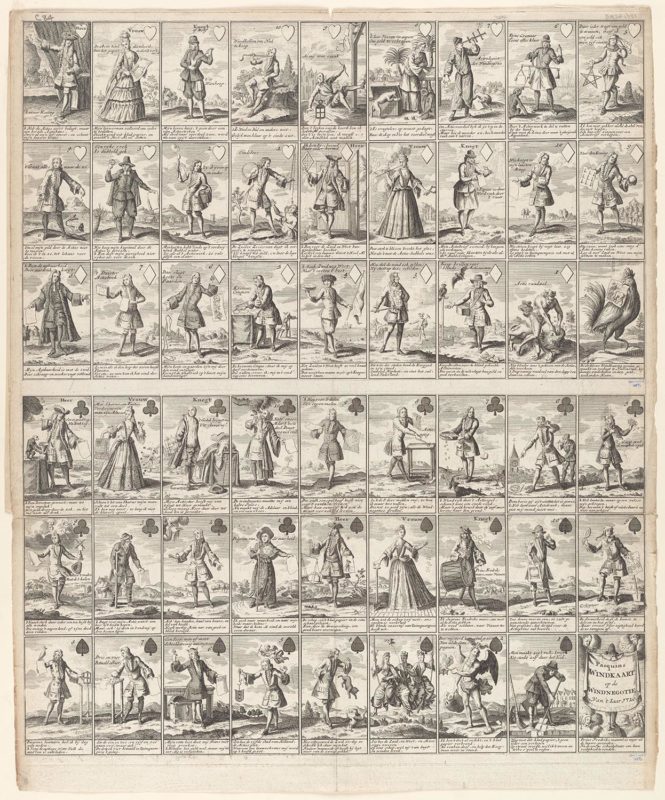

Right now, in a hushed and august third-floor wing of the New York Public Library, a slew of archival prints, caricatures, and notes lampoon the pioneers and losers of the world’s first economic collapse. Dubbed Fortune and Folly in 1720, the free exhibit aims to ‘hold up a mirror to our own age.’ Swap in our recent mania for NFTs and cryptocurrency—and their epic rise and downfall—for the players and faddism of three centuries ago and, lo, history does seem to be repeating itself, but with actual jail-time for some principal architects this time.

The Villains

The star—and villain—of the 1720 crash was John Law (1671-1729), a Scottish gambler turned financier who introduced a new currency—paper money—via the Banque Générale in 1716. It would flood the market and became worthless by the end of 1720.

Law was never arrested for his involvement in the ruinous scheme, but others were. One document from 1723 reveals that the Constable of the Tower of London sought payment for expenses incurred while safe-keeping prisoners, including John Aislabie, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who was convicted of “most notorious, dangerous, and infamous corruption,” and sentenced to five months in jail.

The Con Artistes

Many women actively participated in John Law’s bubble economies, including the French regent’s mistress, Parisian salon-hostess Madame de Tencin, and Lady Katherine Knollys, the niece of Queen Anne Boleyn. Knollys, who became Law’s common-law wife and accomplice, fled to Venice after his “system” collapsed.

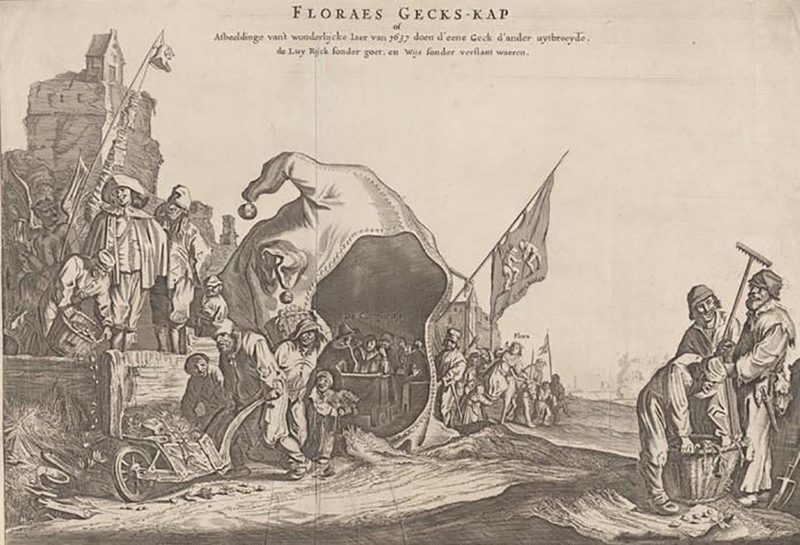

‘Tulipmania’ Returns

The immediate years leading up to the crash of 1720 had been a banner time: In France alone, excited speculation in New World trading companies generated such dizzying wealth—seemingly overnight—the words millionaire and nouveau riche were coined. But by the end of 1720, stock values had dropped so much that investors rioted in the streets of Paris. The boom and bust drew comparisons to Tulipmania, when demand for new and fashionable tulip bulbs first skyrocketed, then collapsed, between 1634 and 1637.

The Losers

Famed mathematician and astronomer Sir Isaac Newton was one of the notable figures who lost big in the crash of 1720. He later mused, “I can count the movement of stars but not the madness of men.” A handwritten note of Newton’s authorizing the payment of stock interest to a financial agent is featured in the exhibit.

The Skeptics

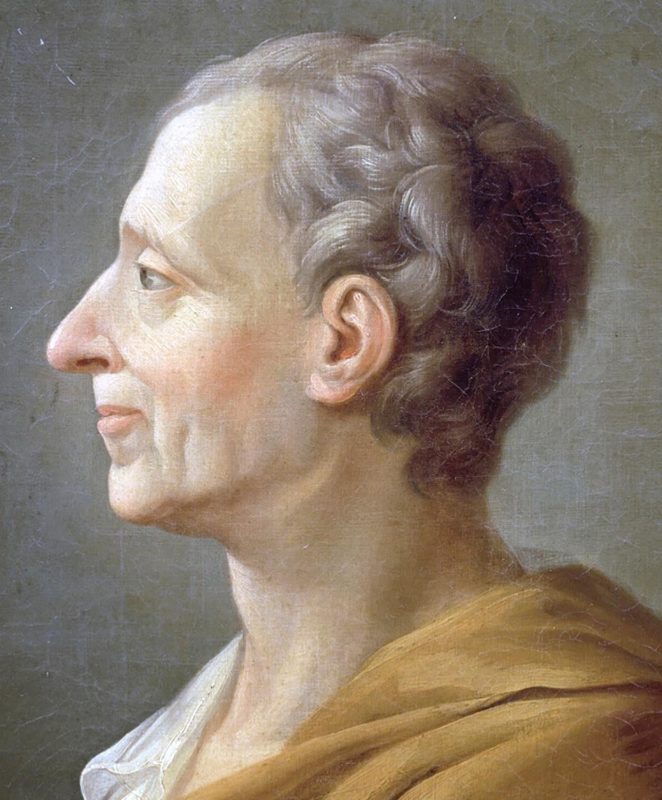

Amidst all the mania leading up to 1720, some did kept their heads about them. As Fortune and Folly in 1720 points out, critics, like French philosopher and novelist Montesquieu, skewered the era’s speculative economy as “an empire of the imagination.”

Fortune and Folly in 1720 runs through February 19, 2023 at the NY Public Library. It’s free.

Lead image by xefstock via Getty Images