Philanthropy

Giving à deux, then saying adieu

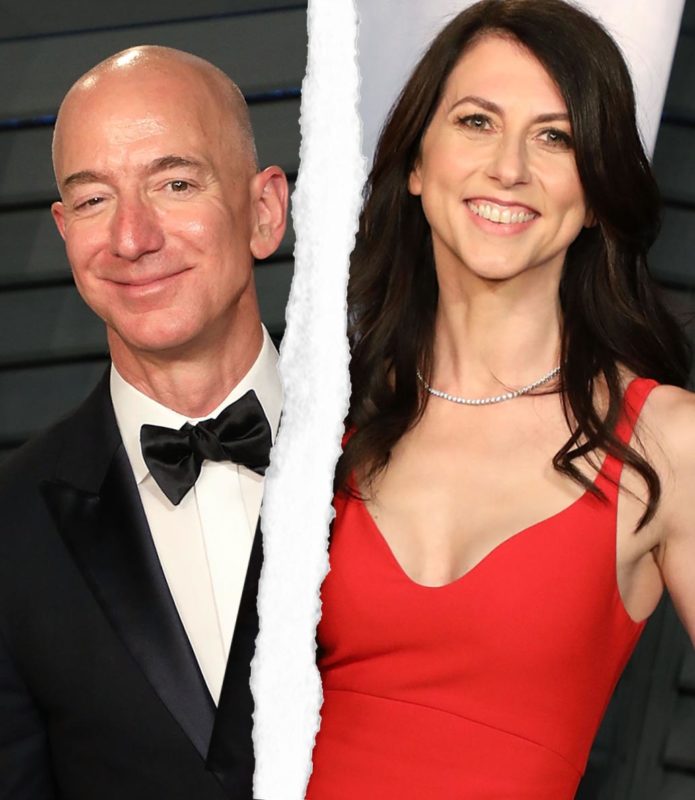

When the rich and powerful split, what happens to the causes they have devoted a marriage to?

Gone are the days of white-haired men living out their final years and deciding what causes to support. Rockefeller and Carnegie and other legacy foundations have given way to Gates, Bezos, and Zuckerberg, the beneficiaries of the tech boom. Giving while living is now the norm.

“There are so many centers of philanthropic power now,” notes Benjamin Soskis, senior research associate at the Urban Institute on NonProfit and Philanthropy, citing some 100,000 foundations in the US currently. “Death used to be the life event that structured giving. You used to give after a full career,” continues Soskis, who has tracked trends in giving for 20 years. “Now people are giving in their 20s, 30s, and 40s right after the IPO.“

This means that large-scale philanthropy is intersecting life in ways it didn’t previously. Think marriage (Prince Harry and Megan Markle); births (Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan); and Divorce (The Gates, The Bezos and, and, and).

Divorce is the life event when charities have the most to lose. For the newly single, newfound financial independence can be an opportunity to forge a new identity but for charities, divorce is often time to worry.

So what happens to the causes and endowments that power couples devoted their marriages to when their union goes bust?

Just as homes, cars, kids are divided up, so too are the tax breaks, donations and swank dinners.

Who gets what is often about optics, notes Raoul Felder, New York’s divorce czar who has represented everyone from Rudy Giuliani to Riddick Bowe to the wives of Martin Scorsese and Patrick Ewing. “Ego is often at play.”

Rarely does this play out in public, according to the experts. Typically such details are worked out behind the scenes by the lawyers.

Heather Hostetter, one of Washington, DC’s top divorce attorneys, has witnessed it all. Say a couple formed a foundation together but now can’t stand to be in the same room, no less a boardroom, or they’ve always gone to x premiere or y annual gala, they’ll need to decide if, and how, they will continue to do so. “If they don’t agree, then they horse trade during the settlement,” she explains. “Lawyers can even negotiate specific dates as to who gets to attend what and when.”

It’s a rare case when a splitting couple’s social aspirations aren’t at odds. Such was the parting of Mercedes and Sid Bass, royalty of New York’s cultural scene for decades, who split in 2011. Five years earlier, the couple had given $25 million to the Metropolitan Opera, its single largest gift at the time. When they split up, Billionaire Bass, having publicly stated he never really liked the opera, retired to his ranch in Texas and happily let Mercedes enjoy her passion for music and retain her role as Vice Chairman of the Met’s board of directors.

More typical however, according to Hostetter, divorce negotiations over charities unfold like a custody battle.

The UK hedge-fund billionaire Sir Chris Hohn and his ex-wife Jamie Cooper may not have the same name recognition as Bill and Melinda this side of the Pond, but their story should serve as a bellwether to other billionaire philanthropists.

When the couple divorced in 2014, Jamie Cooper was awarded £337 million, but a squabble over their philanthropic endeavors ensued. Six years later, a British court ordered Sir Hohn—who had been knighted for his philanthropic endeavors—to fork over an additional £270 million to a charity Cooper had set up.

When Bill and Melinda French Gates announced their divorce in May 2021, the former head of Microsoft was reported to be worth $152 billion. Much of their wealth had already gone toward the Gates foundation targeting global public health initiatives.

The Gates decided to continue co-running their foundation. However, their divorce settlement stipulates that in two years, “if either party feels they can no longer work together,” Melinda French Gates will resign. Given the tax advantages that foundations inherently provide, they can’t simply be undone in the case of divorce. As such, should she resign, Bill Gates will essentially have to buy her out of the foundation and use “personal resources” to fund her philanthropic work—resources that would be “completely separate from the foundation’s endowment.”

“French Gates might have some areas she wants to pursue separately,” suggests Jim Ferris, director of the Center on Philanthropy and Public Policy at the University of Southern California. And she just may have that opportunity.

French Gates has already started putting her money where her heart is, directing donations to causes that empower women and girls.

Before her divorce, she founded Pivotal Ventures, an investment and incubation company to advance social progress in the United States with a specific focus on “expanding women’s power and influence.” (Initiatives have sought to get more women in public office; increase women graduates; fast-track women in the tech sector; break down barriers faced by women and girls of color; and support caregivers.) More recently, post marriage, she teamed up with MacKenzie Scott, ex-wife of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, and now the world’s largest individual donor according to Axios, for the “Equality Can’t Wait Challenge” to accelerate gender equality in the U.S by 2030.

With newly single wealthy women like French Gates and Scott stepping into center stage, an important new gender dynamic is emerging, one that’s challenging decades, if not centuries, of how giving is done. “We now have a coterie of women philanthropists, entrepreneurs, and heirs,” lauds Soskis. “They often chose to focus on women and girls. And they offer an implicit and explicit challenge.”

But it’s Scott’s revolutionary giving strategy that is having the most impact on philanthropy. At the time of her 2019 split with Bezos, Forbes estimated Scott’s worth at nearly $50 billion. She wowed the world by publicly pledging to give away all her wealth during her lifetime.

Scott has already given away more than $12 billion to some 1,200 groups—$2 billion more than her ex committed to combat climate change through the Bezos Earth Fund he established in 2020. Scott made headlines again last month when she donated $436 million to Habitat for Humanity, her single largest gift to date.

What makes Scott so unique is the speed at which she is doling out donations and the way in which she is doing so. Unlike the traditional school of giving—where donors ask charities for paperwork and impose rigorous restrictions—Scott relies on a team that researches nonprofits and charities beforehand. If they pass muster, a grant is given with no strings attached, allowing the recipient to use the money in any way they see fit.

When philanthropy was ruled by an Old Boys network, there were all sorts of conditions attached to the donations, despite repeated pleas from charities to loosen up their restrictions. But with Scott now the highest profile figure in giving, eclipsing many male billionaires, funders across the country are beginning to embrace her style of giving.

Per Soskis, she is providing pressure on others to follow her lead, which could change the entire nonprofit sector. “She makes it impossible to ignore,” says Soskis.

And that is a good thing.

Photo credits: From top, Jeff Bezos and MacKenzie Scott, Taylor Hill/FilmMagic via Getty Images; Melinda and Bill Gates, Kevin Mazur/Getty Images; Jamie Cooper, Andrew Cowie/AFP via Getty Images; Melinda French Gates, Jamie McCarthy/Getty Images for Bill & for the Melinda Gates Foundation; Habitat for Humanity, Brittany Murray/MediaNews Group/Long Beach Press-Telegram via Getty Images; Ada Dev Academy, courtesy of Pivotal Ventures.