At Auction

A Rare Brancusi Comes to Christie’s

Owned by art impresario Rue Carpenter, cofounder of The Arts Club of Chicago, the drawing traces its provenance to the master’s groundbreaking 1926 show in New York.

A rare drawing by Constantin Brâncuși that traces its provenance to the private collection of the visionary woman who cofounded The Arts Club of Chicago over a decade before the Museum of Modern Art opened in Manhattan is coming to auction at Christie’s.

“Brâncuși drawings are incredibly rare to market,” says Allegra Bettini, Christie’s Specialist and Head of Works on Paper Sale. The Romania-born artist is celebrated primarily for his sculpture and was not prolific. “His non-sculptural oeuvre amounts to less than two hundred.”

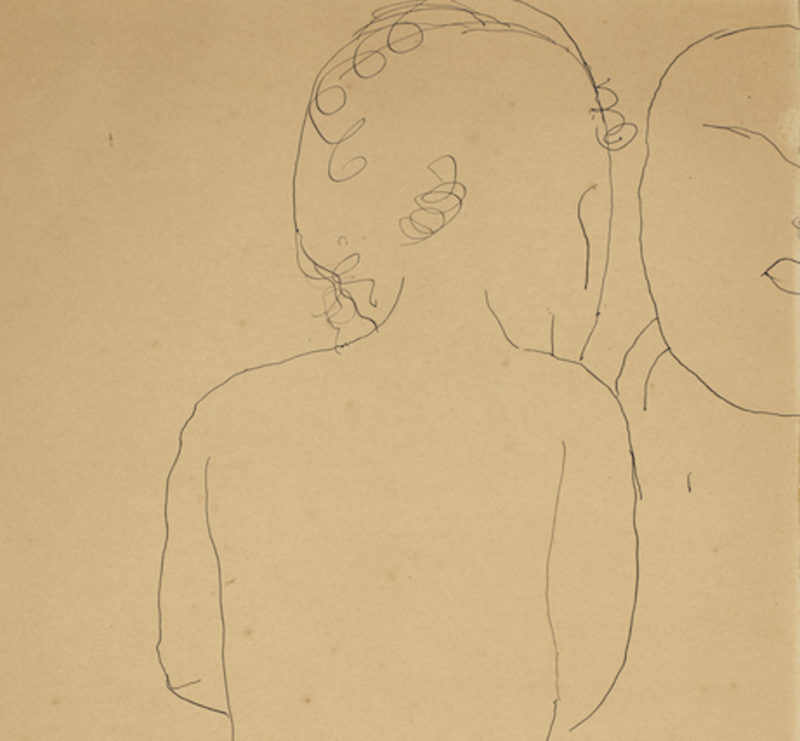

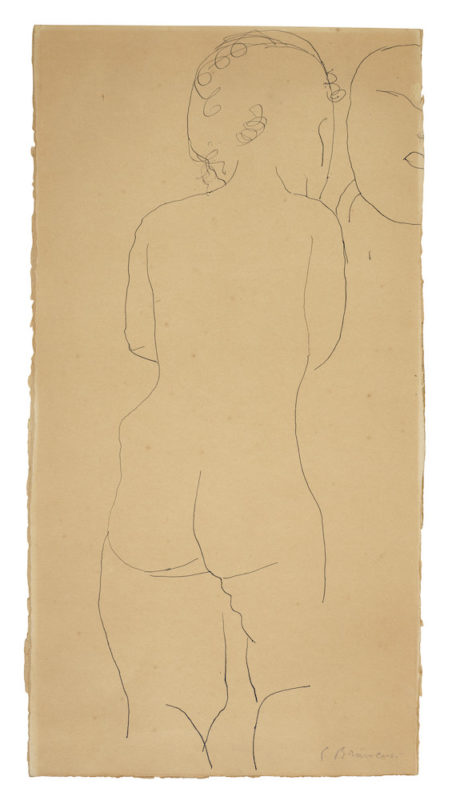

Depicting two babies in pen and India ink on an 18⅞ x 10 inch card signed on the bottom right, Sans titre (Deux enfants) comes from the private collection of interior-designer and philanthropist Rue Carpenter and carries an estimate of $25,000 to $35,000.

A gift from the artist, the drawing has been in Carpenter’s family since the 1920s. Last shown publicly in Chicago in 1930, it will be on view for the first time in almost 100 years in Christie’s New York galleries ahead of the Impressionist and Modern Works on Paper and Day Sale on Saturday, May 14.

A “most brilliant woman”

A contemporary of Elsie de Wolfe—often credited as the first American interior designer—Rue Carpenter was extolled as a decorator par excellence by Billy Baldwin. She decorated the Casino Club in Chicago, The Arts Club of Chicago, and the Elizabeth Arden salon on New York’s Fifth Avenue, with its legendary red front door.

Rue and her husband John Alden Carpenter, one of the first composers to deploy jazz rhythms in orchestral music, also led a glamorous cosmopolitan life. They socialized in Paris with Cole Porter and Gertrude Stein, and were lifelong friends of Gerald and Sara Murphy.

In 1923, the Carpenters were guests of the Murphys—whom F. Scott Fitzgerald immortalized in Tender is the Night—at their Villa America in Cap d’Antibes, along with Picasso and his wife Olga. A month later, referencing a photograph of Carpenter, her daughter Ginny, and Sara Murphy on the beach, Picasso drew Trois nus féminins.

Arthur Meeker, a midcentury chronicler of Chicago’s upper set described Carpenter as “an original genius . . . the most brilliant woman I have ever known.” He added, “You never could tell whom you were going to meet at the Carpenters—Stravinsky or Karsavina, Marcel Duchamp or Mrs. Patrick Campbell…Like as not they’d be sitting on the cushion next to yours…guessing charades or playing musical chairs—just not being celebrities.”

A Controversial Artist

Brâncuși selected Sans titre (Deux enfants) for his first major one-man show in New York, organized by Marcel Duchamp at the Brummer Gallery in November 1926.

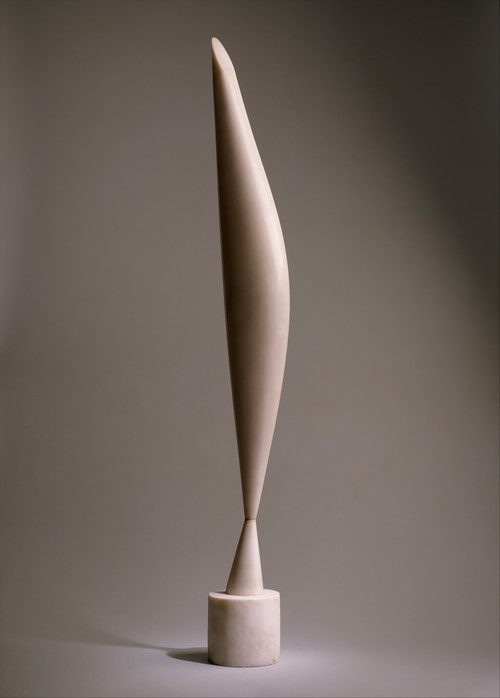

The controversial exhibit sparked a lawsuit that would radically shift public perception—and the legal definition—of abstract art, after U.S. Customs refused to allow the artist’s sleek bronze sculpture, Bird in Space, to enter the country duty-free. Officials declined to recognize it as art.

It was only after vehement protestations by Duchamp himself, Brâncuși’s friend who’d organized the exhibition and accompanied his artworks from Paris, that customs released the work on bond. They nevertheless imposed the standard 40% tariff for manufactured objects, categorizing Bird in Space under “Kitchen Utensils and Hospital Supplies.”

The cultural clash between the cognoscenti and the unconvinced unleashed a torrent of negative press for Brâncuși, who was roundly mocked and derided. This compounded the notoriety he had gained in Paris in 1920 when he scandalized the Salon des Indépendants by submitting Princess X, a large bronze sculpture of a gleaming phallus. The offending object was an homage of sorts to Princess Marie Bonaparte, the grandniece of Napoleon I who consulted Sigmund Freud in her elusive quest—alas in vain—to achieve female orgasm.

Gregarious and intrepid, Carpenter’s abiding mission was to bring to the windy metropolis what Brâncuși’s babies represented. As the artist stated in Eric Shanes’s Constantin Brancusi (Abbeville Press): “Art must give suddenly, all at once, the shock of life, the sensation of breathing.”

And thus, undaunted by the hullabaloo in New York and Paris, Carpenter invited Brâncuși to bring his “utensils” for a one-man show at The Arts Club of Chicago in 1927.

According to Carpenter’s great-granddaughter, Pauline Hubert, the artist gave her great-grandmother the sketch of the two babies as a thank you present for arranging the exhibition. His affectionate crayon and graphite portrait of Carpenter, which also featured in the New York exhibition, is now in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Celebrated primarily for his sculpture, the drawings by Brancusi share a special insight to the artist’s vision and practice,” says Bettini. “In this case, I love to see how the simplicity of his line connects to the reduction of form seen in his three-dimensional works.”

The last Brâncuși baby drawing to come to Christie’s fetched $47,500—almost double its low estimate—in 2017. The artist also seems to be having a moment these days.

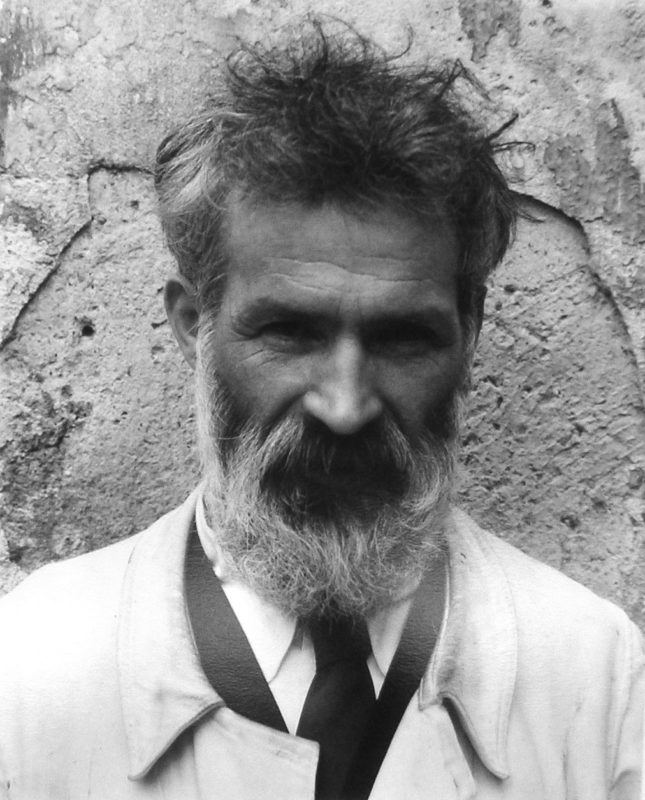

Peter Greenaway, the writer and director of The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover and his whimsical The Draughtsman’s Contract, recently released a new trailer for his upcoming movie, Walking to Paris. Set at the dawn of the 20th century, the story follows the 27-year-old Brâncuși, a fledgling artist, as he makes his arduous 18-month pilgrimage on foot to the crucible of world culture.

Fittingly, Greenaway’s trailer ends with a clip of the bearded artist, captivated as a baby takes its early steps on a vast dining table in Paris, savoring “the shock of life.”

Brâncuși’s Sans titre (Deux enfants) is currently on view at Christie’s New York galleries and will be offered at Christie’s Impressionist and Modern Works on Paper and Day Sale on Saturday, May 14.