Trending

It’s My Party And I’ll Kvell If I Want To

The return of the big ticket bar mitzvah.

Once upon a time, back before the ravages of Covid, the heights of Manhattan bar mitzvah madness seemed to be getting ever-higher. For Jewish private school families living in certain precincts of the Upper East and West Sides, these parties—held mostly downtown—were costing well into the six figures, and the major blowouts—the kind that practically every kid, let alone adult, wanted to go to—were even crossing over into the sevens.

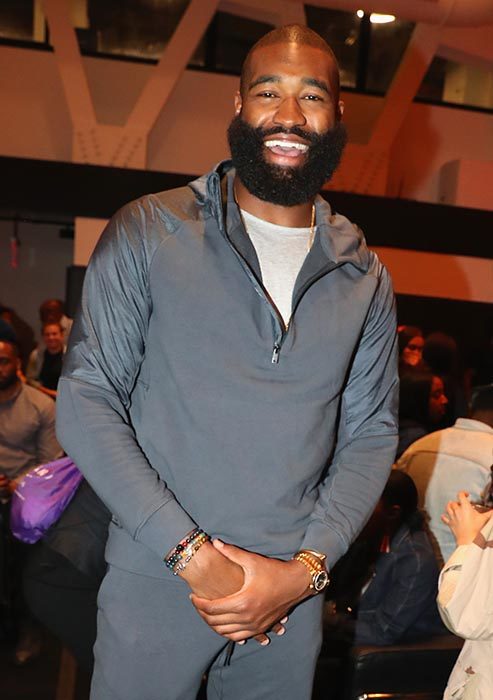

Back then, not only might a bar mitzvah have a Knick in attendance—say Kristaps Porziņģis or Kyle O’Quinn (who, due to appearing so frequently at such events, referred to himself as “Bar Mitzvah Man”)—but there were even performances by the likes of Drake, Ariana Grande, and Cardi B. It was all so fun, so over the top, and also so sufficiently common that Billboard magazine—not exactly known for its bar mitzvah coverage—felt compelled to run a story called “How to Get Flo Rida to Play at Your Bat Mitzvah.” The answer: Why, you call a celebrity booker, of course.

As entertainment costs ballooned, so too did those of the bar/ bat mitzvah pièce de résistance and bane of Jewish mothers everywhere: the montage. Where once, say, back at the start of this century, montages were relatively simple video slideshows of the bat mitzvah kid’s life—chronologically ordered photos of them, their siblings and extended family, plus school friends, camp friends, and a couple of staged shots from trips to Disney and Paris (though not, you know, Paris Disney)—somewhere along the way this kind of film got deemed boring. Perhaps even déclassé. And so a whole subgenre of films I am hereby naming cinémitzvah was born.

Whereas a montage made with the help of say, the Montage Maven of Westchester (yes, this is an actual person) starts at $1,500 ($5,000 if you want the Gold package), the cost of cinémitzvah is exponentially higher.

“People do spend a lot on a montage, easily $25,000 or more,” says Joe St. Cyr, owner of Joseph Todd Events, a high-end Manhattan mitzvah planner whose Instagram hashtag is #goywonder. “As opposed to sending in some photos, doing some transitions, and putting in some music with a sober mind, other people may opt to create a time capsule to record interviews of friends and relatives, go do costuming, makeup, off-site locations, scripts, creating a small film that has a theme.”

Cinémitzvah’s first, and perhaps still only, viral video is titled, The Devil Wears Prada: The Bat Mitzvah Years. An eight-minute-long, high-production-value film starring, and created for, an Upper East Side girl by her film producer uncle—whose oeuvre includes such titles as “The Secret Life of a Celebrity Surrogate,” “The Donor Party,” and “The Au Pair Nightmare” – TDWP: The Bat Mitzvah Years features a fur cape-wearing top magazine editor-cum-bat mitzvah girl who is “more powerful than Kim Jong-Un.” Or was, rather, until her classmate turns out to be having a bat mitzvah on the very same day. (Alas, a typical real-world conflict that cannot only generate much angst, but, on those rare occasions when such a conflict cannot be resolved, Montague and Capulet–like warring parties.)

Meanwhile, of course, the real bat mitzvah bogeyman turned out not to be the rival classmate, but rather Covid-19, which ground the whole mitzvah industry to a halt. Though never the services, which, at the height of the pandemic, simply moved to Zoom.

“You’ve got your Rodeph Sholom,” says St. Cyr. “Your Park Avenue Synagogue. They each had their own protocols. In the beginning, the family could go as a pod and get dressed up and do the bimah,” he says, referring to the platform on which mitzvah ceremonies typically take place. “The rabbi would be in a separate room, or not even in the synagogue.” There were no parties at this point, says St. Cyr. “It took a while for the event planners and mothers to figure out what to do.”

The first solution, he says, was the custom Bar Mitzvah in a Box which, simple though it might seem, was actually not that simple at all. “You can’t send a day-old bagel to people, G-d forbid!” says St. Cyr. “Chilled whitefish? It has to be delivered that morning, between 9 and 11, and it can only be in Manhattan. What do you do with New Jersey? We’d have to send those guests something else, maybe some really excellent cookies and brownies. Some of the kids from the elite private schools live in the outer boroughs or deepest, darkest Queens. But we didn’t want them to be left out. Who doesn’t want a nosh? There’s lots of sensitivity issues. The box itself comes and it doesn’t look like much.”

(Photo by Johnny Nunez/Getty Images for Think450)

Meanwhile, says St. Cyr, the arrangements were actually dizzyingly complex. “I was in Montana at this time. I couldn’t gather with my staff. Logistically, it was as much work to plan a small delivery as a big bar mitzvah. There were so many logistics that it was hard sometimes for me to explain why I still had to get paid this fee. What I did do, I absorbed the cost of the labor.”

As Covid entered a still pre-vaccine, but somewhat calmer, phase during that first summer and fall, St. Cyr began working on small celebrations, what he calls “Micro Mitzvahs,” the lion’s share of which took place at people’s beach homes in the Hamptons. Others were held on the North Fork, in Bernardsville, New Jersey, and the Hudson Valley.

For these events, the mitzvah parents often had to get permission to host from their child’s head of school. “Everything was week to week,” says St. Cyr, “day to day.” People had to take Covid tests, and Purell and masks were on offer. “No one got prosecuted,” says St. Cyr, “no one went to jail. But there was that shame factor.”

Typically, for a Micro Mitzvah, there would be about 30 adults and 40 kids, under a tent on the family’s property. “It was a small, curated group,” says St. Cyr. “Just the closest family and friends.” There would often be a basketball court set up, outdoor games, and “lots of fun food. That didn’t mean it didn’t cost $150,000,” he notes. “People wanted the celebration. They were desperate for conversation, especially the chattering class. There was a lot of gossip that had to be traded.” People were even sitting on each other’s laps, as he remembers it: “I have never seen people communicate so effectively, so quickly, and so joyously in my life.”

Now, two and a half years into the pandemic, the big bashes are all back on. Are they more over the top than ever, I ask St. Cyr. “I don’t know how much more decadent we can get,” he tells me.

But the biggest change, he says, is that the parties are now virtually all about dancing. And the most popular music, as it turns out, is from before the pandemic, songs like “I Love It,” “Shut Up and Dance,” and “Party Rock Anthem.” “I think it’s nostalgia,” says St. Cyr. “I also think we picked up where we left off. The music that was created during the pandemic was not experienced as a group phenomenon.”

Adding to the more festive atmosphere, he says, is the fact that the kids are no longer on their phones as much, a change that is most noticeable with the boys. “It used to be that the girl parties were better,” he says, “but now the boys are on the dance floor all night. The boys are loving it. They don’t wear blue blazers anymore, just sneakers and khakis or sneakers and jeans. White shirts. These kids are not as jaded. They’re just loving it because they’re coming out of a dark period.”

Hero image: A bar mitzvah celebrant is thrown in the air at his party. Photo courtesy of Chad David Kraus (@chadkrausphoto, www.chadkraus.com)