Book Club

What to Read Now

A British bookshop asked renowned writers for their recommendations.

To celebrate their 20th anniversary, the London Review Bookshop invited 20 authors to share the titles they think we need to weather the next 20 years—and why.

Here, five writers’ choices.

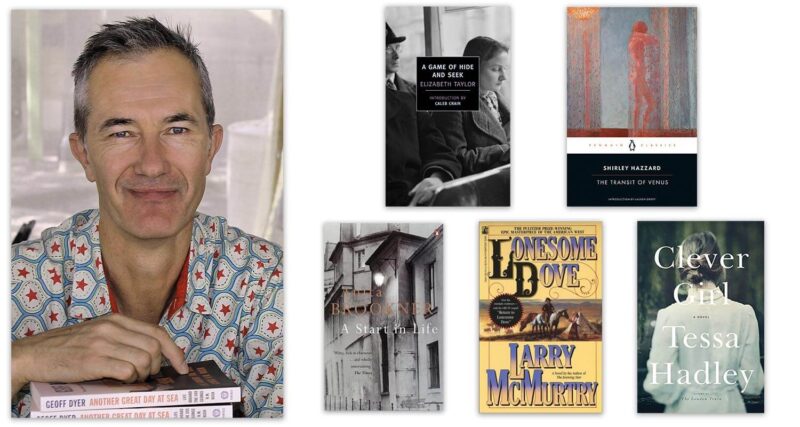

Geoff Dyer

That Sort of Stuff

Since no-one foresaw the sudden collapse of the Soviet Union or the 9/11 attacks it seems best to eschew books with any predictive quality.

It’s probably wise to avoid topicality and trends as well and to concentrate on the things we know won’t change, which will be as sure to happen in the next 20 years as they did in the period 1833–55: falling in and out of love, marriage, adultery, friendship, the longing for adventure and escape (often thwarted), illness and death, disillusionment, infirmity, that sort of stuff.

So I could just choose five novels by Anita Brookner but I’ve expanded the net to avoid any suggestion of narrowness. Oh, and I’ve included the Larry McMurty because whatever else happens, we will always want books—about anything—that offer the experience of complete immersion.

A Game of Hide and Seek by Elizabeth Taylor

The Transit of Venus by Shirley Hazzard

A Start in Life by Anita Brookner

Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurty

Clever Girl by Tessa Hadley

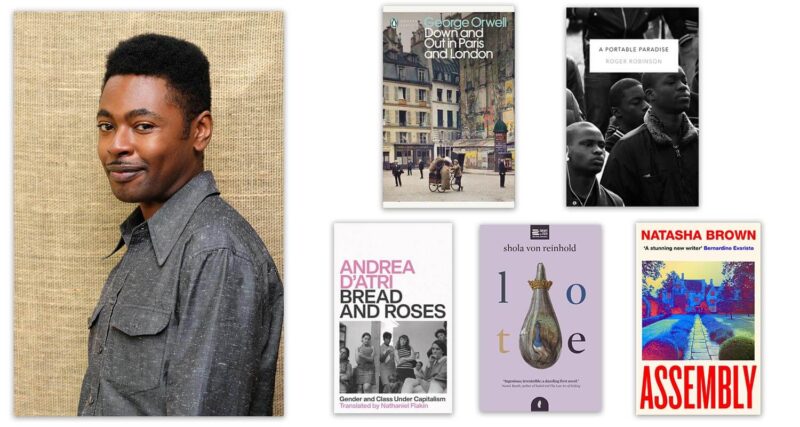

Paul Mendez

Work Experiences

The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated trends in automation and The Great Attrition, which have seen workforce numbers decline due to advances in technology and waves of bitter resignation.

As industries strive to meet net zero and employees balance stagnant wages (and race-/gender-based wage inequality) against spiraling living costs, student debt and housing woes, the world of work as we know it appears unsustainable.

These five books speak for key workers and migrant laborers, those enduring institutional sexism and racism, and individuals seeking the dream odyssey in the mundane, across the intersections of race, class, gender, and sexuality.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell

A Portable Paradise by Roger Robinson

Bread and Roses: Gender and Class Under Capitalism by Andrea D’Atri

Lote by Shola von Reinhold

Assembly by Natasha Brown

Mary Beard

The Past is All We’ve Got

Thinking hard about the past is often a more productive way of facing the future than gazing into a crystal ball. So, my choices aren’t about climate change or major shifts in the imperial world order or carefully calculated predictions of disaster.

Tacitus’s Annals, written in the second century CE, is probably the most acute analysis of political corruption and the corrosive effects of tyranny that there has ever been, however. And for fundamental questions about what “civilisation” is, there are no more thought-provoking and influential reflections than those in Homer’s Odyssey.

For essential background to issues that are not going to go away in the next 20 years, Richard Ovenden’s Burning the Books is a cautionary tale about knowledge under attack throughout history, and David Olusoga’s Black and British did more than any other book (or television programme) to dispel the fantasy that there were no people of color in the UK until Windrush.

And for a dire warning of the consequences of not thinking hard about the lessons of history, a good dose of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is required. As I heard the Spanish novelist Antonio Muñoz Molina observe recently: it might be difficult to learn from the past, but the past is all we’ve got, so we must make the most of it.

The Odyssey by Homer, translated by Emily Wilson

Annals by Tacitus, translated by Cynthia Damon

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Black and British by David Olusoga

Burning the Books by Richard Ovenden

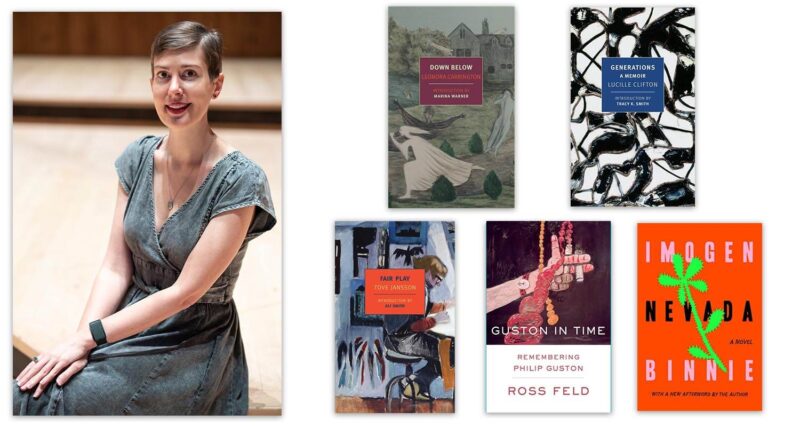

Patricia Lockwood

Armpit Books for a Cold Era

For this sort of emergency (the next 20 years) I like books you can slip into an armpit and have them be warm in less than a minute. These are ones I’ve kept closest to my bed and for the longest time. If anything unites them, it is the idea of making art in the cracks, hunkered down with others of your kind and waiting to come under the rule of the generous law.

From Philip Guston to Ross Feld: “I think you are writing about the generous law that exists in art. A law which can never be given, but only found anew each time in the making of the work. It is a law, too, which allows your forms (characters) to spin away, take off, as if they have their own lives to lead—unexpected, too—as if you cannot completely control it all. I wonder why we seek this generous law, as I call it. For we do not know how it governs—and under what special conditions it comes into being. I don’t think we are permitted to know, other than temporarily.”

Down Below by Leonora Carrington

Generations: A Memoir by Lucille Clifton

Fair Play by Tove Jansson, translated by Thomas Teal

Guston in Time by Ross Feld

Nevada by Imogen Binnie

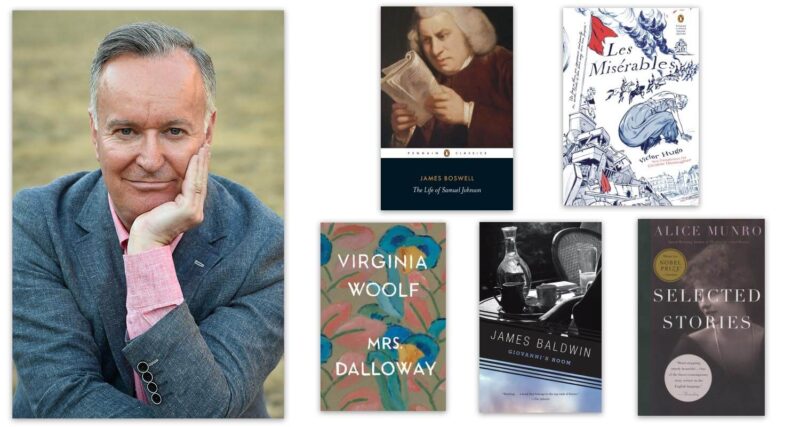

Andrew O’Hagan

The Human Chain

Over the next 20 years, the ability to sort imagination from reality will become a matter of intellectual survival. We already wonder what it was like to be relatively unmediated, as humans, but the future will be taken up with the civil liberties of robots. “Are they civilians?” The David Humes of 2043 will ask, “and does their liberty stem from us?”

The phrase “common humanity” may come to seem like a rigorous denial of the optics. And at that point, I believe, we will begin to look at the stylists and what it was they caught in human specificity—a look, a proclivity, a feature of the blood, a nuance of personal growth.

This might offer a beautiful counterbalance to the bloodless stylistics of Artificial Intelligence. Humanness: a failing, open-hearted, dreaming hunk of moral value, before uniformity and algorithms came to position each of us as a marketing story.

Artificial intelligence may send us back to find what was natural about our own intelligence. We may look, as Zola did, at the means by which we were circumstantially or economically programmed, but the new, technological cultural wars will make it all seem fragile. We will come to see what it was that we shared back then, in the exaggerated miasma of our differences.

The Life of Samuel Johnson by James Boswell

Les Misérables by Victor Hugo, translated by Christine Donougher

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin

Selected Stories 1968–1994 by Alice Munro

Hero photo courtesy of London Review Bookshop.

Author photos: Geoff Dyer, Larry D. Moore, CC BY-SA 4.0