Art & Culture

Tony Cokes exhibit at Dia Bridgehampton

New video installation probes the politics of color.

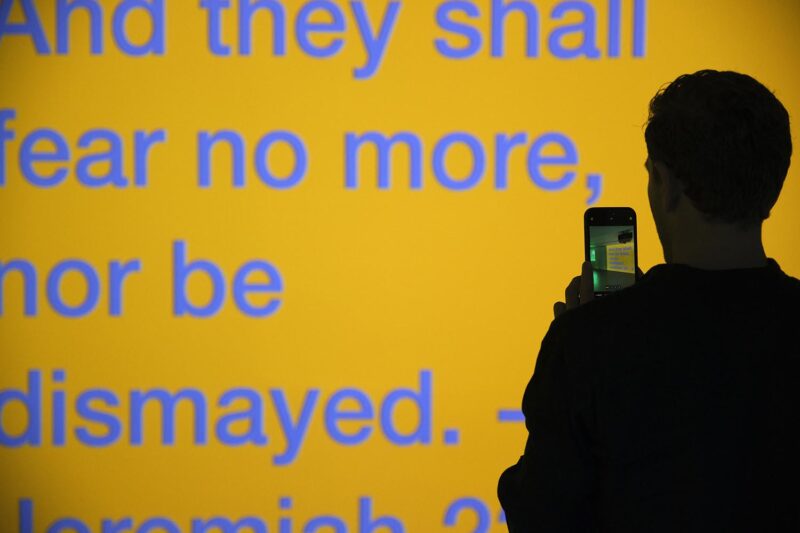

As soon as you walk into the new Tony Cokes exhibit at Dia Bridgehampton, it feels like you’re being immersed in a kind of spiritual conversation about color itself.

It could be because the building, once a turn-of-the-century, shingle-style firehouse and then a Baptist church from 1924 to the 1970s, carries a certain aura.

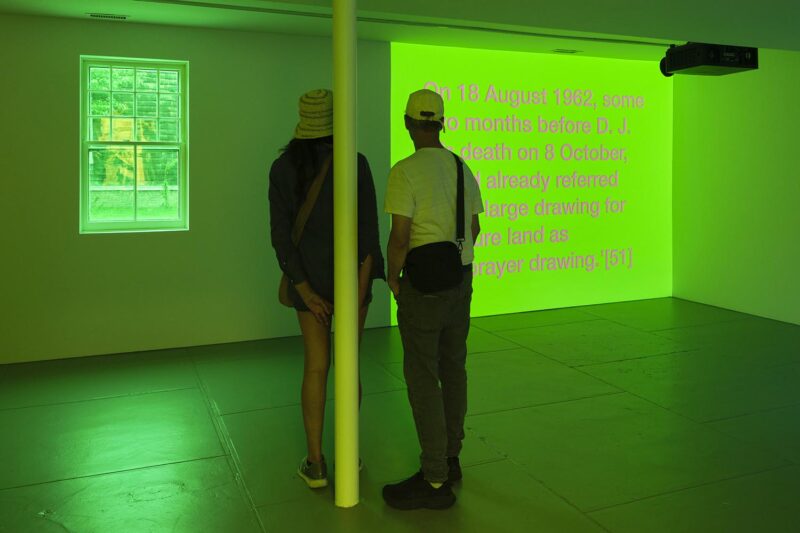

Or, it might be because Cokes’ two floor-to-ceiling video installations feature texts focused on theory, criticism, philosophy, journalism, and social media, which unfold against a soundtrack of music of the Black diaspora. This fusion of soul, blues, gospel, and electronic music amplifies the Nine Sculptures in Fluorescent Light, a permanent installation on the floor above, created by the American minimalist artist Dan Flavin, who designed the space to permanently house his work.

As for Cokes, who has remixed text, music and documentary images into videos since the late 1980s, color is recast not as a neutral agent but as a “vehicle for negotiating the politics of visibility and invisibility,” according to an exhibition description.

The exhibit—which runs through May 2024—”probes the politics of color and what it means to use color in this way,” says Jordan Carter, curator at the Dia Art Foundation. “There’s a lot of interesting context in terms of seeing Tony’s work in conversation and dialogue with the permanent installation on the second floor.”

Cokes is notably one of the first non-local residents to exhibit at Dia Bridgehampton in recent years. A “post-conceptualist” and professor in the department of modern culture and media at Brown University, his work is in the collections of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (among others). But it is the juxtaposition of his work within the historic importance of the space that will have the most impact on anyone who visits the museum.

“The work offers a way to get a richer understanding of the space itself and the layered history of its past lives,” Carter says.

The exhibit ends, in fact, in a second floor gallery that was created to hold memorabilia from the church’s history, including an open Bible, vintage photos, the original doors, and a neon cross.

“Tony is thinking through and asking the questions, ‘What does this space mean?’ ‘What do histories mean, and how do they come together in this moment presently?’” Carter says. “He does it in a way that’s animated—in a vibrant and energetic way with music that gives it this club atmosphere. It’s like reading while dancing.”

While Carter hopes anyone walking through the space comes to it without a preconceived notion, he also believes that every visitor will get out of it what they may.

“There’s an energy to the work, the feeling that being in the space is like being a member of a new congregation,” he says. “I hope people will have their curiosity piqued.”

In an extension of the exhibition, the work continues on two 61-foot-tall Shinnecock Monument electronic billboards, operated by the Shinnecock Indian Nation.

“These large billboards play fragments of the piece as digital images,” Carter says. “As you drive down Sunrise Highway you’ll see text that speaks to the popular media Tony employs and critiques in his work.”

Hero photo of Tony Cokes by Don Stahl