Royal Insider

The Extraordinary Life of Lady Pamela Hicks

The remarkable story of a viceroy’s daughter, queen’s bridesmaid—and design legend’s wife.

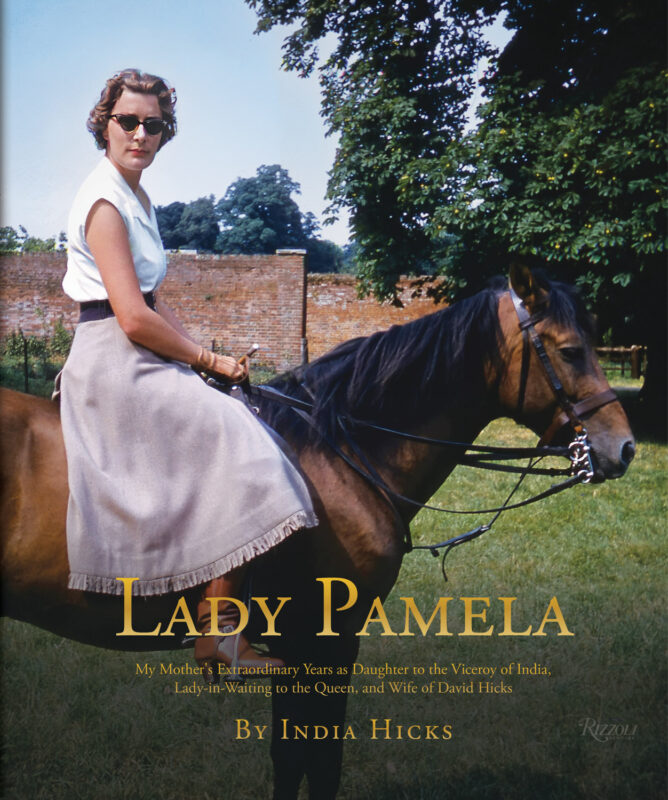

In her new book, Lady Pamela: My Mother’s Extraordinary Years as Daughter to the Viceroy of India, Lady-in-Waiting to the Queen, and Wife of David Hicks, India Hicks relates how her mother, Lady Pamela Hicks—a British aristocrat and part of the royals’ inner circle—lived a life framed around the themes of service, loyalty, and duty.

Although largely based in England, Pamela moved to India with her parents while her father, Earl Mountbatten, oversaw independence from British rule, and traveled the world as a companion to the Queen.

As a child during WWII she was sent to New York with her older sister for their safety.

In 1940, my mother was only eleven years old when it was unexpectedly announced that she and my aunt were being sent to America until the end of the war. They were going to stay in New York with someone called Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt. They were going, it was explained, because their great-grandfather, Ernest Cassel, was Jewish. My mother nodded wisely but didn’t really understand why that meant they had to leave. She imagined it had something to do with Hitler, but she didn’t know for sure.

My grandparents booked them passage to the United States aboard the SS Washington, the last ship to take children across the Atlantic before the crossing became too dangerous. The ship was so full that some of the passengers had to sleep in the drained swimming pool.

After a week at sea, they woke at dawn to see the Statue of Liberty. Much taller than my mother had imagined, seeing it up close was really thrilling. Clearing customs, my mother was given her first taste of what being an “alien” meant. Having been born in Barcelona, she was made to stand in a different line from my aunt and the rest of the British evacuees. The customs official told her that under no circumstances could she work in America.

An extremely well-dressed woman introduced herself as Mrs. Vanderbilt’s secretary. Even my mother’s young eyes could see how fashionably she dressed—far better than anyone back home. The woman guided them into a waiting car, and they were whisked toward 640 Fifth Avenue. The facade of Mrs. Vanderbilt’s residence was enormous and imposing and the inside was no less so. The hall was cavernous, all marble floors and surfaces, and featured a huge malachite vase that was even taller than the girls. (My mother took me once to see this years later, in the entrance hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

A small, queenly form, Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt wore a long silk dress with a bandeau swathed around frizzy gray curls. “Girls,” she said, “you must call me Aunt Grace.”

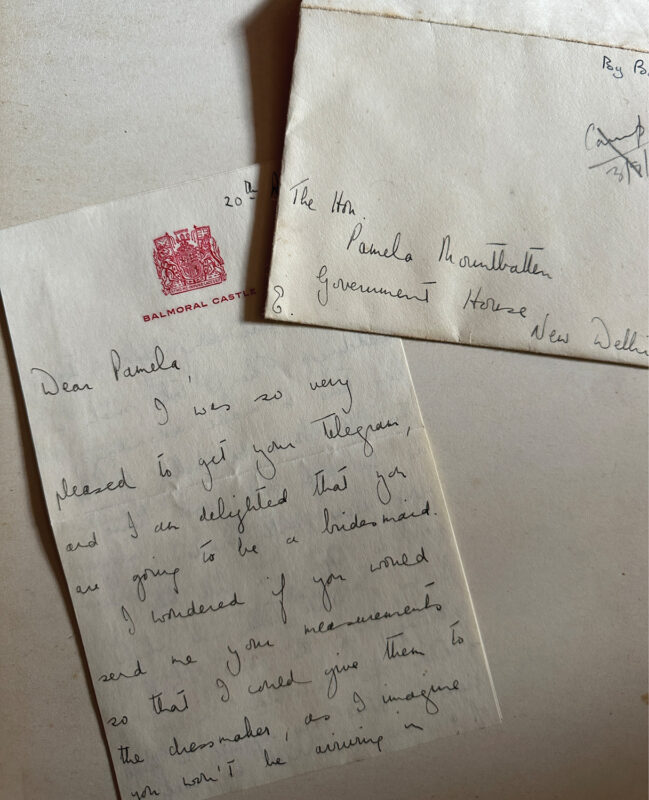

All through that hot summer of 1940, my mother and aunt were shunted among the Long Island summer houses of New York’s kind society hostesses, getting used to their new surroundings, unfamiliar American expressions, and new routines. My mother wrote copious letters to my grandparents from Mrs. Vanderbilt’s villa-style Newport, Rhode Island, residence on Bellevue Avenue. My grandparents insisted that all letters be numbered in case some of them arrived out of sequence or were lost at sea. As the war progressed, my mother and aunt felt guilty being so safe when their parents were not.

My mother couldn’t unburden her feelings of homesickness to my grandmother, as she was so easily upset; in their home life, it was always best to share worries with my grandfather. Thus, my mother drew a picture for him and posted it with letter number 14, showing “Pamela Carmen Louise Mountbatten (still, stranded on a raft floating to you!!)” There were three flags on this vessel: one simply had the word help, the second displayed the Union Jack, and the third was a pair of billowing bloomers labeled “white pants (sign of distress!)”

The jolliness was a poor attempt to hide the ever-growing homesickness she was feeling.

Despite attending school, being with my aunt, and receiving the kindness of the impeccably behaved New Yorkers, my mother couldn’t settle, especially as news of my grandfather’s “adventures”—family code for life-threatening events—reached them, namely when his ship, HMS Kelly, was bombed and he was presumed dead, news that was luckily dispelled.

My mother felt bad, living in what seemed like another world and thinking she should be back at home suffering like everybody else in England. She wasn’t exactly unhappy, though—there were too many new experiences and things that made my aunt and her laugh. For example, it was important for Mrs. Vanderbilt to be seen at the opera and she decided to take my aunt, the eldest, with her—that is, to some of the opera.

Eager to make an entrance, Mrs. Vanderbilt would arrive at the end of the first act, whereupon she would enter her box with the diamonds of her sumptuous necklace ablaze as the lights went up for the intermission. After she felt that she had been noticed sufficiently, she would take her seat. At the end of the second act, Mrs. Vanderbilt felt she had done her bit and would go home, so my aunt got to know only the second act of each opera.

Letters from home were becoming less frequent and they often arrived in a mixed-up order. My grandmother wrote to tell the girls that the baby wallaby had died, then they received another letter from her that said he was doing very well. A week or so later a third letter arrived to say that it had been born.

Hero photo courtesy of India Hicks