Blooms of Bloomsbury

London’s Garden Museum: Digging into the Past

This very British sanctuary caters to enthusiasts who care not only about the planting, but also the history of their passionate pursuit.

“The first pure joy of the garden,” Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary on May 31, 1920, “. . . weeding all day to finish the beds in a queer sort of enthusiasm which made me say, this is happiness.”

Indeed, several extraordinary women of Woolf’s circle—Vanessa Bell, Vita Sackville-West, and Lady Ottoline Morrell—found joy and solace in the soil; and now, their enthusiasm is celebrated in Gardening Bohemia: Bloomsbury Women Outdoors, at London’s Garden Museum until September 29, 2024. The first exhibition on the blooms of Bloomsbury has objects on show ranging from Sackville-West’s boots to Bell’s paintings.

The Garden Museum is the world’s only museum of the art, history and design of gardens and is to be found in the most unlikely of places, the ancient church of St-Mary-at-Lambeth, next to Lambeth Palace—home of the Archbishop of Canterbury—and close to the Houses of Parliament.

Once there you can enjoy soused mackerel, horseradish and soda bread, one of the very English delicacies at what has been called “the best museum restaurant in London.” Diners look out on a leafy cloister garden designed by Dan Pearson where, in a 17th-century tomb, the John Tradescants—two of Britain’s earliest gardeners—are buried. The Tradescants, elder and younger, were gardeners to King Charles I and Keepers of His Majesty’s Vines and Silkworms.

The younger traveled to Virginia from 1628 to 1637 and brought back to England over 200 new plants, including magnolias and the tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera), as well as the ceremonial cloak of Chief Powhatan—the father of Pocahontas and the head of the Powhatan Confederacy of Native Americans (now in the Ashmolean). The elder was head gardener to Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury at Hatfield House, the Jacobean palace 15 miles from London where Queen Elizabeth I spent much of her childhood.

The late Dowager Marchioness of Salisbury—who came to live at Hatfield in the 1960s and redesigned its gardens in the 17th-century style—was closely involved in the creation of the museum.

One day in the 1970s, her friend Rosemary Nicholson wandered into St Mary’s looking for the tomb of John Tradescant. Horrified to discover that the Church of England and Lambeth Council were about to abandon the church and its historic tombs (Captain Bligh of mutiny on the Bounty is buried here), she decided to save it. Lady Salisbury agreed to help, and together these two redoubtable ladies succeeded in raising the necessary money.

They then hit on the idea of creating a Museum of Garden History.

Lady S’s address book of aristocratic friends and relations came into play. People were persuaded to dig about in their potting sheds and outhouses for gardening relics. Early exhibits included Victorian wheelbarrows, thumb watering cans, leather boots for pony-pulled lawn mowers, and 19th-century tools that include a high point of Victorian prudery, the cucumber straightener.

In 1977, they officially opened the museum. Early trustees included Lord Carrington—once Britain’s Foreign Minister—and Lord de L’Isle VC, former Governor-General of Australia. Another supporter was Sir George Taylor, director of Kew Gardens.

Here, you can study the papers of Russell Page, Penelope Hobhouse, and many others; see a film about Beth Chatto, and hear a lecture about guerilla gardening (which is essentially growing food or flowers in abandoned, and usually unauthorized, public spaces—the gardening equivalent of squatting.)

In the shop you will find gardeners’ favorite tools. You might also see an exhibition of Lucien Freud’s plant portraits or a reconstruction of the filmmaker and poet Derek Jarman’s fisherman’s shack on the shingle shore of Dungeness.

Fashion and Gardens in 2014 was the first exhibition to explore the relationship between fashion and garden design, from the age of Queen Elizabeth I to the present catwalks of Fashion Week. Alexander McQueen’s spectacular lilac silk organza evening dress that resembles an open flower was shown alongside Valentino’s black scrolled opera cloak inspired by the wrought iron gates of Italian Renaissance gardens. Rose in Fashion in 2022 showed a 1991 Comme des Garçons dress embellished with red cashmere petals.

The Museum’s royal patron is King Charles III. Queen Camilla, a keen gardener, is a frequent visitor to the museum’s British Flowers Week—an event inspired by Shane Connelly, the royal florist who designed the arrangements in Westminster Abbey for the coronation. Six chosen florists erect fantastical themed flower arrangements in the nave of the church using seasonal British-grown flowers. This year’s event runs from June 3 to 9.

The museum has forged links to 55 schools in the local borough of Lambeth. Each week, 100 schoolchildren and members of the community assemble in the museum to engage with aspects of horticulture, from bulb planting to flower painting.

Every summer for ten years the Garden Museum has left London for a weekend to hold a literary festival in a country house with pavilions set up in private walled gardens to hear Britain’s garden writers and designers discuss their enthusiasms. Past venues include Chatsworth in Derbyshire and Parham House in West Sussex; this year’s festival will be held at Sezincote House in Gloucestershire on June 23 and 24.

Guests wander across green lawns and might end up in an old library to hear Robin Lane Fox, the Oxford classics don and Financial Times gardening columnist speak about “Thoughtful Gardening” or Richard Mabey on “Weeds.” At Petworth House a few elderly guests, after dining at sunset in the Grinling Gibbon Carved Room hung with landscapes by Turner, walked out into the twilight shouting “Tonight everything is possible” and leapt into the Capability Brown lake.

Leaping into cold water is something Museum director Christopher Woodward does to raise vital funds for the museum as it is an independent charity that receives no government funding. He has swum the Hellespont (the strait that separates Asian Turkey from European Turkey) which inspired the descendant of Byron’s publisher John Murray to make a generous donation.

When the Museum was in danger of closing permanently due to Covid, Christopher swam a sponsored 50 miles across rough seas from Cornwall to the Scilly Isles. For safety he was accompanied by a boat and told to get out of the water every few hours and eat bananas to keep up his strength.

Such activities and energy show his dedication as a director. It also inspires optimism that the extraordinary Garden Museum will continue to delight visitors for many more years.

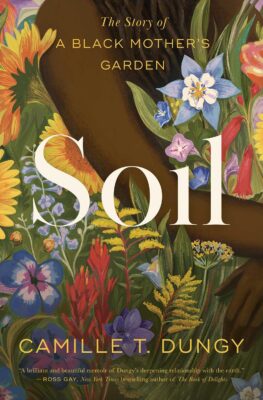

Hero photo of British Flowers Week All For Love installation by Courage & Dash