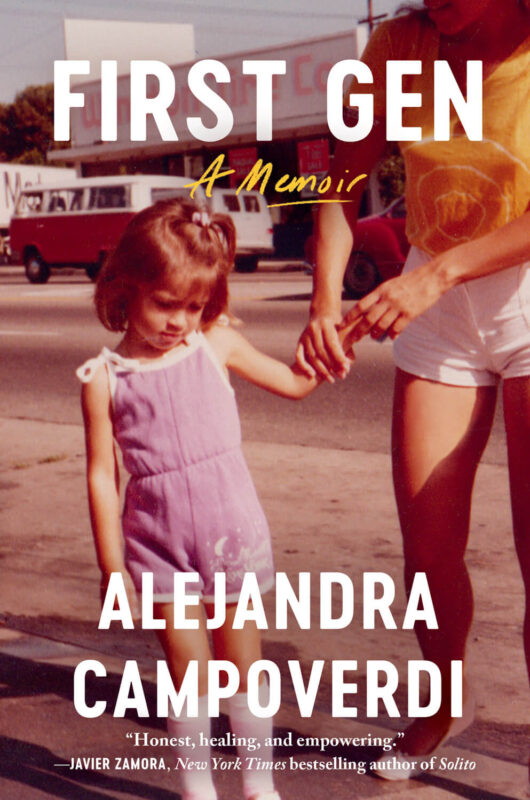

Books we love

Should I go to Harvard?

In this excerpt from her moving memoir, a first-generation Mexican American explains how accepting admission to the country’s most elite academic institution wasn’t a simple “Yes.”

The first few weeks after I received my acceptance letter, I lost myself in daydreams of strolling to class through Harvard Square under fiery autumn leaves, hands in the pockets of a beige trench coat. I’d get to be Ali McGraw in Love Story after all.

I had never achieved something in my life that was so universally celebrated. Robert started using me as an example in his GMAT classes (from waitress to Harvard after taking this course!), my coworkers at the foundation seemed to regard me as more capable and perhaps smarter, and even my aunts said “Whoa” when I told them the news.

My mom found a way to work my acceptance into every conversation she had. (“Have you met my daughter Alejandra-who-got-into-Harvard?”) When a white package with a crimson crest arrived in the mail, I ripped it open blissfully, running my hand over the smooth card stock and breathing in the scent of elegant paper.

But my euphoria was short-lived. Right behind the photos of students studying on well-manicured grass were my financial aid documents. Or I should say document, because there wasn’t much to it. No grants, no scholarships, and no need-based accommodations. In order to attend the Kennedy School, I’d have to take out over $150,000 in student loans. Coupled with the USC loans I still hadn’t paid back, going to Harvard would mean saddling myself with over $200,000 in debt. Plus interest.

I felt queasy as I stared at the tuition breakdown in my hand. It was so much money. Could I really go through with this? I had always assumed a Harvard education would rubber stamp anyone’s future prospects, but now it seemed like there was a chance it could limit mine. Would I ever be able to buy a house, or even a car, with such heavy debt? I was staying afloat with my foundation salary, but I made under $40,000 a year, which made saving impossible. When would I ever see the kind of money that would allow me to make a dent in a sum as large as $200,000?

Blindfolded Cliff Jumping. That’s the best way I can think of to describe what this level of risk-taking felt like to me. While everyone must weigh and navigate some level of risk throughout life, First and Onlys are often faced with difficult choices that have astronomically high stakes. That’s because it’s less common for us to have safety nets (family financial support), parachutes (built-in professional networks through our families), or bungee cords (savings) to make the big leaps—like starting a business or exploring a passion project—feel more manageable, as well as to cushion the landing after any natural falls or failures. And on top of the inherent danger of jumping off a cliff, we are often doing so blindly, without any sense or expectation of upcoming obstacles as we hurtle directly toward them. We rely primarily on faith, grit, and nerve.

Going to Harvard would mean betting big on the earning potential of a future version of myself, someone I wasn’t certain I was capable of becoming. Looking around my bedroom at every possession I owned in the world—my childhood four-post bed, a small television, a closet filled with clothes from discount stores—it didn’t feel like I was the type of person who should be taking financial risks of epic proportions. And it didn’t help that I had another perfectly great (and safer) option.

In an effort to be thorough, or out of paranoia, I had submitted business school applications into the double digits. In addition to the Kennedy School, I had also been accepted to several MBA programs, and they all came with scholarships of some kind; Harvard was the only school that didn’t offer me a dime. USC had even offered me a full ride. Staying close to home in LA, attending my alma mater, and graduating with zero additional debt was an incredible—and way less risky—option. Not to mention the ultimate question: Would moving across the country to start a new school retrigger my panic attacks?

Dr. Freeman and I had been working together for nine years at this point—doing a combo of cognitive behavioral and exposure therapy. And I hadn’t had a panic attack since freshman year of college. As a part of my exposure therapy, I was even flying again—on short plane rides, all under an hour—to Northern California for my job at the foundation.

But moving to Massachusetts on my own would be a huge test, and I wasn’t sure how I’d do. What if I fainted at orientation (again)? Or had to drop out after a few weeks because I couldn’t sit through class or take exams without hyperventilating? There were a lot of unknowns and my mom was understandably worried.

“If you go to USC, you won’t owe any money,” my mom said, looking over my financial aid letter. “And then you’ll be home. Close to us.”

She didn’t have to say the next part out loud for me to know what she was alluding to. She was thinking about my anxiety. I could see it on her face as she knitted her brow, handing the paperwork back to me. “That just seems more doable.”

It was certainly more pragmatic, but my mom couldn’t grasp the full picture of what a degree from Harvard could mean for someone like me. More and more, the advice I was receiving from my family felt contradictory. As is the case for many First and Onlys, my mom often encouraged me to reach for the stars. At the same time, she wanted me to stay securely and reliably close by. Her fears of the unknown seemed to surface each time I faced a critical crossroads.

When I cut back my hours waiting tables to take GMAT prep classes, my mom warned I should think twice before compromising such dependable income. Considering Harvard versus USC presented a similar conundrum. She wanted success for me, but her fears stood in direct opposition to the calculated financial risk it would take to get there, and she voiced those fears at the very moments when I sorely could have used a pep talk instead.

There is a focus on the immediacy of earning money that often looms over the families of First and Onlys. It’s a mindset formed in reaction to their own experiences, but the reservations they express can nevertheless feel hurtful at times.

Harvard was not just a school; to me, it represented something far greater. Yes, a world-class education, but I also viewed a Harvard degree as the single most powerful professional “validator” I could earn. As a First and Only, gaining a globally recognized credential that could serve as testimony to my potential seemed especially vital to have. It could only lead to open doors.

When I landed at USC my freshman year, I had no shorthand to ease my acceptance into elite spaces; I didn’t grow up in Orange County or have a parent who was a celebrity. But now, I had an opportunity to reset the playing field. I believed that having Harvard on my résumé would legitimize my belonging in a way that my life circumstances never could. Forget social ladders; this was my seat on a rocket ship—if I didn’t pass out in public first. I knew what I wanted to do, but could I go through with it?

On the day before the deadline to commit, my hands trembled as I reviewed the online loan documents. The amount I was borrowing was more than I’d earned in the previous five years combined. I would owe the entire cost of my tuition plus the total cost of my living expenses for two years—housing, food, books, everything. How much was I really willing to bet on myself?

Excerpted from the book First Gen: A Memoir by Alejandra Campoverdi. Copyright © 2023 by Alejandra Campoverdi. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

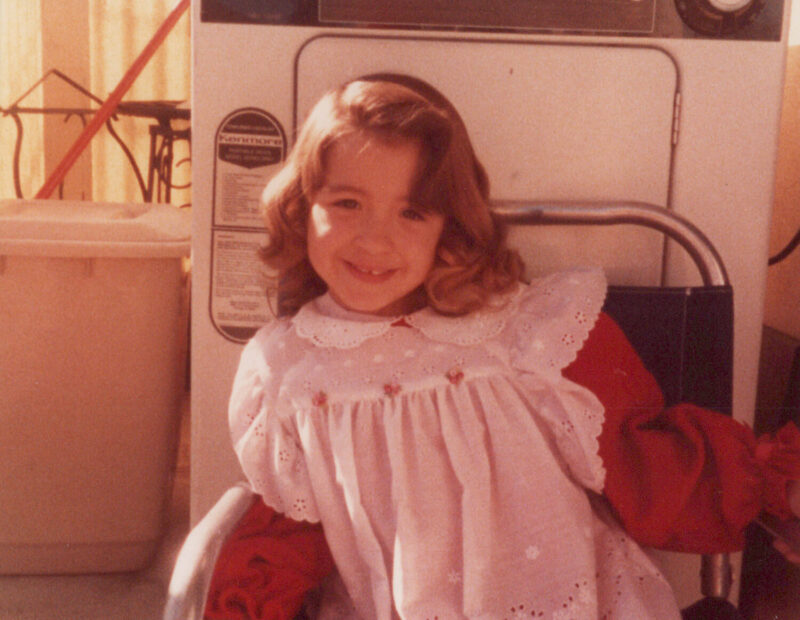

Hero photo courtesy of Alejandra Campoverdi