DP Books

The greatest jewel thief who ever lived

A charming con artist and cat burglar, Arthur Barry targeted New York’s elite, pulling off the most brazen and lucrative heists of the 1920s.

In a span of seven years, the Jazz Age’s most successful burglar swiped diamonds, pearls, and other gems worth almost $60 million today from the bedrooms of New York’s wealthiest. Dubbed “the aristocrat of crime”, Barry robbed only the rich, claiming, “If a woman can carry around a necklace worth $750,000, she knows where her next meal is coming from.”

He befriended the likes of the Prince of Wales and Harry Houdini, and stole from the homes of bankers and industrialists, polo players, and heiresses—including the Rockefellers in Greenwich, Connecticut in 1926.

Diamonds sparkled in the beam of Arthur Barry’s flashlight. Four pieces of exquisite jewelry had been left on top of a dresser at Owenoke Farm, the hotel-sized country home of Percy and Isabel Rockefeller. As he scooped them into his silk-gloved hands, a woman screamed—the Rockefellers’ 22-year-old daughter, Winifred, had passed the bedroom and spotted him. He ducked through the window. Servants and the night watchman rushed outside in time to see him drop to the ground and run toward the edge of the estate. Barry was soon in his car and speeding away.

The bold theft from the nephew of Standard Oil founder John D. Rockefeller made headlines across North America in October 1926. Percy had inherited his fortune from his father, Rockefeller’s brother William, a cofounder of the petroleum giant and a leading New York banker. At 48, Percy was one of the world’s richest men, with a net worth estimated at $100 million. A major Wall Street player, he was a director of dozens of corporations, invested in banks, railroads, utilities, and copper mines, and grew richer as stocks soared skyward. “A capitalist of first magnitude” and “a shrewd and highly versatile financier,” the newspapers said.

His wife, Isabel, was the daughter of James Stillman, the former president and chairman of New York’s National City Bank and William Rockefeller’s closest friend and business ally. Stillman had been a multimillionaire in his own right, and, after he died in 1918, so was Isabel.

The marriage in 1901 of these “Scions of Millions,” as the Baltimore Sun described the couple, was the second to unite two of the wealthiest and most powerful families of the Gilded Age; Percy’s brother was married to Isabel’s sister.

Barry’s quick foray into the bedroom netted him four items worth $25,000: a gold wristwatch, a gold bracelet, a pendant, and a ring, all set with diamonds.

Isabel Rockefeller had no idea what they were worth. “I didn’t buy any of them. They were all given to me by my father,” she told the New York Daily News. She had received the watch when one of her daughters was born, and the rest were presents to mark other special occasions. “For that reason they are worth more to me than all the other jewelry I own.”

The police suspected the crime was the work of the burglar who had swiped $30,000 in jewels a month earlier from Freestone Castle, a Tudor-style mansion surrounded by nine acres of grounds only three miles from Owenoke Farm, home to a retired shoe manufacturer Duane Armstrong and his wife, Jane. It was. Barry’s haul that night had included a finger-width ten-carat diamond ring.

For Percy Rockefeller, who avoided the spotlight, the break-in and the press attention were a nightmare. Owenoke Farm—the New York Times later called it “one of the outstanding country residences of Southern Connecticut”—was his refuge. He had joined the exodus of New York’s superrich to Greenwich, transforming a rural hamlet into an estate-studded community that was said to boast the highest per capita income in the United States. The vast grounds kept the world away. The imposing mansion oozed grandeur and sophistication, with 64 rooms spread over three floors. It was a showcase for the couple’s extensive collection of museum-quality fine art and antiques, including 18th-century Flemish tapestries, oriental silk rugs, Chinese porcelain, statuettes, paintings, and carved walnut furniture dating to the Renaissance.

It was also Rockefeller’s bunker. The Wall Street tycoon “lived in mortal dread of earthquakes,” a Greenwich-area newspaper later revealed.

Even though it had been more than a century since a major quake rattled Connecticut, he took out a million-dollar insurance policy to cover earthquake damage and instructed his builders to encase the mansion in three-foot-thick walls of reinforced concrete.

A skilled second-story man, it turned out, posed a greater threat than earthquakes to Rockefeller’s sanctuary and his family’s privacy. Newspapers made light of the burglar’s hasty exit, publishing a photograph of Winifred Rockefeller alongside a cartoon of a bob-haired flapper wielding an umbrella and chasing a shabby-looking masked man. Rockefeller hired the renowned William J. Burns International Detective Agency to try to hunt down the man who had invaded his fortress-like home.

The break-in, Barry later revealed, was an “impromptu venture.” Working alone, he had set out to rob another estate in the area, but it was swarming with visitors. On the drive back to New York, he spotted Owenoke Farm. Only later, it appears, did he discover that it was Percy Rockefeller’s estate. His plan, he explained, had been “to touch nothing.”

He would slip inside, explore the layout, and return another night for the valuables, as he had done many times before. When he spotted the jewelry, however, it was too tempting to resist. His payoff for a few minutes’ work was a haul worth more than $400,000 today.

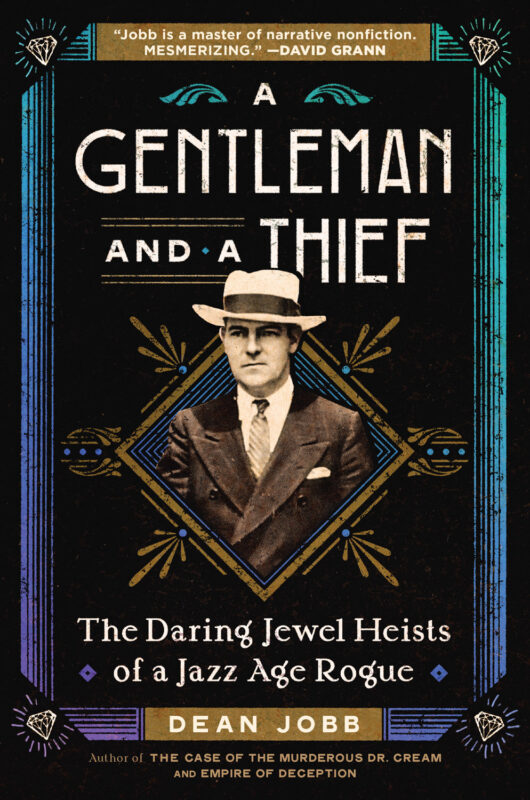

Hero photo of Arthur Barry, left, handcuffed to a guard after his arrest in 1927 courtesy of Dean Jobb