DP Books

Untold Power

The fascinating rise and complex legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson.

She hated the title “First Lady,” preferring to be known by the name on her calling cards: Mrs. Woodrow Wilson. But for some months at the end of 1919 and beginning of 1920, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson held the most political power of any First Lady in history.

Even today, by the simple fact of her marriage, the First Lady is one of the most famous and publicly scrutinized women in America. That was dramatically more true a hundred years ago, when many fewer women had the opportunity to achieve national prominence in their own rights.

Yet the role of First Lady comes with no job description, no constitutional duties or legal guidelines. She is, therefore, a blank slate for the projections of a critical public. As scholar Molly Meijer Wertheimer puts it, “all First Ladies become symbols of American womanhood and as such they are expected to conform to the public’s image of the ‘ideal woman’ of their times.”

But the times, of course, they keep a’changin’. So not only can a First Lady rarely rely on the precedents of her predecessors, but sometimes the public’s expectations change in real time while she fills the role. Edith became First Lady when she married President Woodrow Wilson at the end of 1915, after the death of his first wife, Ellen.

Unlike wives who rise up through the political ranks with their husbands, she didn’t have the luxury of an on-ramp to national attention. She had to develop a public persona overnight. She chose the role of devoted second wife, living only for the health and success of her brilliant husband. She also wanted to be known as a gracious social presence, in contrast to the earnestly awkward first Mrs. Wilson.

Edith was praised for her choice as soon as the engagement was announced. “Mrs. Galt is regarded as a woman of rare beauty and charm,” the Washington Evening Star wrote approvingly. “Those who have known her best predicted today that she would be, as the first lady of the land, a popular hostess as well as a comfort and support to the President in his daily work.” If she was hoping to reflect the 1915 feminine ideal, she chose her image perfectly.

But the years Edith served as First Lady, 1915–1921, saw profound changes in women’s social roles. World War I required women to take on traditional male jobs and do them well. Suffrage activists pushed for recognition of women’s rights, not only securing the vote but also challenging the notion that public life was the exclusive domain of men. And while Edith was never a suffragist, she did take on more public roles than any First Lady before her.

She was the first to stand behind the president when he took the oath of office. She was the first to accompany her husband on business calls with cabinet secretaries. She was the first to travel abroad while her husband was in office. She was welcomed and celebrated by royalty in England and Italy in a way no leader’s wife had been before.

She was admired globally for her public visibility, which was all still very much in the service of her husband, never for her own agenda. When she accompanied her husband to Europe in 1918, one English reporter gushed, “No queen could have had a more queenly manner, no great lady could be more gracious, no woman more utterly winning than President Wilson’s wife.” Edith kept that clipping in her scrapbook.

So when her husband collapsed from a stroke in October 1919, no one should have been surprised when Edith inserted herself between his sickroom and the public. She would protect him from anything that might make his condition worse, which included most of the duties of the presidency.

From the day of their marriage she had cast herself as his devoted helpmate, there to make his life easier both in private and in public, and she would continue that role until her husband recovered.

For a little while, that was enough. A sympathetic public worried over their fallen leader and supported his wife as gatekeeper. But what no one knew, what they could not know because Edith controlled the truth so closely, was just how sick Woodrow was, how many decisions he could not make, and how long his illness lasted.

For weeks, he was almost totally incapacitated. For months after that, he was weak, easily confused, with slurred speech, limited vision, and a useless left arm. He tired early and was sometimes unable to control his emotions. He slept a lot. Meanwhile, it was Edith who met with cabinet secretaries, Edith who drafted public statements, Edith who made decisions about who could visit her husband, what issues to tackle, and which to ignore.

As history has revealed just how thoroughly and how long Edith maintained control over the executive branch, Americans have professed themselves amazed that this unambitious woman, this wife who wanted nothing more than to serve her adored husband, had the confidence, brains, and cunning to pull off a conspiracy of this magnitude.

But anyone who pays the slightest bit of attention to Edith before her 1915 marriage shouldn’t be surprised at all. Edith’s obituary in 1961 described her as “a most retiring woman to that date, she entered public life in that peculiar white-hot glare that surrounds the White House in a near-election year.” This is typical of the accounts that completely fail to even attempt to understand Edith, painting her as a not-very-bright country mouse who magically became the nation’s most powerful woman overnight.

Many adjectives can accurately describe Edith, but retiring is not one of them. She was fierce, clever, gracious, funny, loyal, and brave. Also petty, snobbish, jealous, and bigoted. She had a somewhat fickle regard for the truth. These are not character traits she developed in the “white-hot glare” of public attention. Her whole history reveals a woman of uncommon shrewdness, ingenuity, and a little ruthlessness. Were she a man, her story would be celebrated as an up-by-your-bootstraps American dream.

An Appalachian girl from dilapidated southern gentry without much formal education, Edith managed to move to Washington on her own as a teenager and thrive in the flashy society of the nation’s capital in the Gilded Age. Beautiful and popular, she tripped lightly through romantic attachments before they became too serious. When she eventually married, she did so for stability and security, not love.

She became the first licensed woman driver in DC and blithely ignored traffic rules as she tooled around town in her electric car. After her first husband died, she took over his jewelry business and made it profitable. She enjoyed years as an independent woman of means, beholden to no one, traveling the world and pleasing only herself.

She prided herself on being the bedrock of her family, supporting her mother and sister and employing her three youngest brothers. When she caught the eye of the recently widowed president, she made it clear his desperate romantic pursuit would be much more successful if he augmented his mushy love notes with discussions of foreign policy.

While the president was smitten from their first date, Edith dragged her feet on marriage, hesitant to give up her independence and fretful the public would think she coveted the office, not the man. Maintaining the monthslong facade that Woodrow was mentally perfect and fully capable of executing the duties of his office was, for Edith, entirely in keeping with her history.

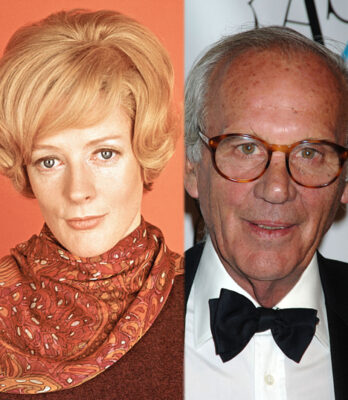

Hero photo: Edith Bolling circa 1886–1896. C.M. Bell Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons