Butterfly migration

The monarchs are coming!

Another orange wave will soon descend upon New York City, but this is one you will want to see.

It wasn’t only birdwatching that soared in popularity during the pandemic. As more people took to the great outdoors, butterfly tracking also gained new fans amongst naturalist hobby seekers. And one of the most fascinating of these winged beauties is the monarch—soon to arrive in the northeast after overwintering in Mexico.

While most butterfly species hibernate, the eastern monarch is unable to survive cold northern temperatures and has a unique, two-way migration similar to birds. Last fall, around 500,000 set off from the northeast on a journey for warmer central Mexico that could be as long as 2,500 miles. But what’s completely fascinating—and mysterious—is the teamwork involved here.

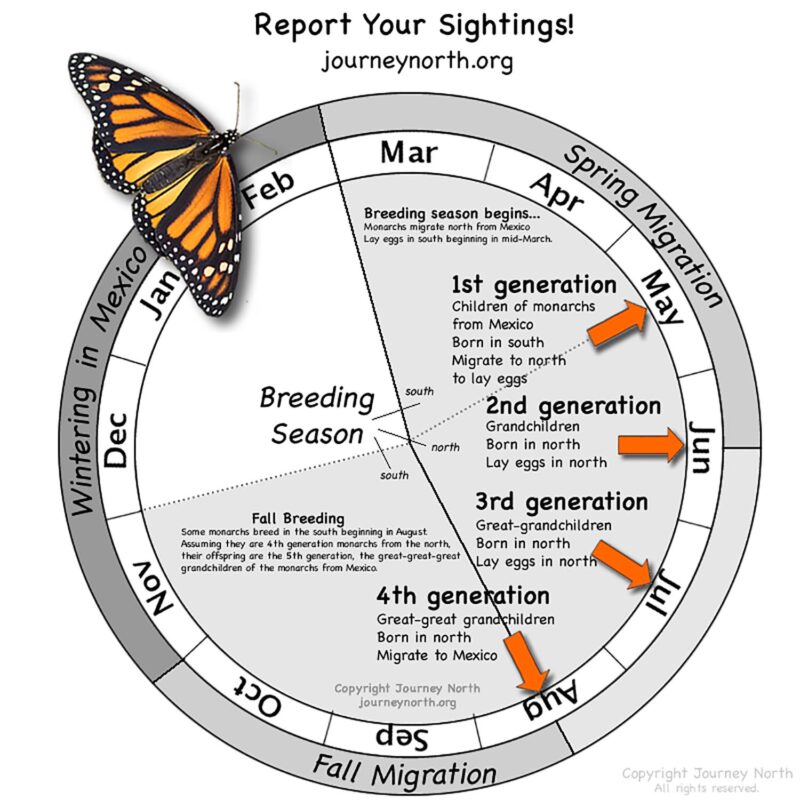

No single butterfly completes the entire round trip. While one group of butterflies may return to exactly the same spot—even the same tree—as their relatives from last year, they are not the same individuals.

As noted in the National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Butterflies, female monarchs lay eggs for a new generation during their northward migration. Depending on the distance traveled, it is their children (or grandchildren) who arrive in the north. And one or two subsequent generations then lay eggs before the fall migration begins. So the butterflies leaving for Mexico may be the great-great-grandchildren of the ones who set off from there in the spring.

Butterfly lovers all over the country track the March departure from Mexico and share migration information in anticipation of their arrival; usually they reach New York in early June. You can check nationwide sightings (and report your own) on Journey North’s interactive map.

If you haven’t spotted a monarch yet this season, you aren’t alone. In years past, we would have seen thousands by now, but their migration has slowed and reports of the butterflies along the eastern coast are down. The monarch was recently classified as “Endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) due to habitat loss.

Inwood Butterfly Sanctuary founder, Keith DeCesare has made it his mission to do everything in his power to help save the monarchs. “A modern-day canary in a coal mine, monarch butterflies are an indicator species,” warns DeCesare. “They signal when something in our environment is out of balance and serve as a warning for our own environmental health. As they are threatened with extinction, we must understand that we are also at risk.”

The sanctuary strives to spread awareness, increase host plant supply and give people the opportunity to observe the monarch life cycle. In addition to viewing huts, they have created an adopt-a-butterfly program allowing monarch enthusiasts to take caterpillars home to watch the transformation.

Although they are slow to come, they are coming. And there’s time for you to create your own sanctuary by creating a space for monarchs to lay eggs and multiply. Head to your local nursery (or the side of your favorite wildflower-strewn backroad) and acquire some native milkweed. Although many flowers will attract the adult butterflies, monarch caterpillars only eat milkweed. The most common species native to New York are Asclepias syriaca (Common milkweed) and Asclepias Tuberosa (Butterfly weed).

Once your butterfly garden is open for business, prepare yourself for the fascinating monarch life cycle. But butterfly beholder beware: monarch tracking is highly addictive. Expect to pass your time petal-peeping your way over blossoms and leaves trying to catch glimpses of tiny (pinhead-sized) eggs and various stages of the larva, praying that a predator or disease hasn’t cut short the cycle of the larva you found the day before. You will find yourself skipping your morning Wordle to check your chrysalises.

Although the cycle sequence is always the same—egg to larva to chrysalis to adult (butterfly)—the timing varies (ranging from nine to 15 days) based on temperature. The payoff is worth the wait as you watch those giant orange and black wings unfold and shake out of the shell, flying off to start the cycle once more. And the ultimate payoff can’t be overstated—we can’t survive without our pollinators.

DeCesare speaks for all of us “monarchists”: “We are anxiously awaiting to see our first monarch of the summer—and I know we aren’t alone.”

Hero image: created by merging photos by Robert Landau and Alexander Spatari via Getty Images