DP BOOKS

Lily Bart’s Hat Shop

What if the most tragic women characters in 19th century fiction did not end up quite as their authors imagined?

It is said that Gustave Flaubert wove his novel Madame Bovary around a press cutting he read in a local newspaper—the sorry tale of a provincial doctor’s wife who, unable to face the consequences of debt and adultery, took poison and committed suicide. It is my belief that gloom, and a passion to punish the frivolous Madame Bovary for the vulgarity of her sins, clouded the great writer’s judgment. He was reading about attempted suicide, not suicide.

The story has come down to me through members of my own family, that though in shame and desperation Emma did indeed cram arsenic into her pretty mouth, Justin the apprentice had wisely taken the precaution of liberally mixing the stuff with sugar and she survived.

Black bile poured out of her mouth, true: her limbs for a time were mottled brown, the desecration of her marriage vows took visible and outward form—but there God and Flaubert’s punishment ended—Emma lived. And if man’s punishment came hot upon the Almighty’s—poor pretty Emma went to prison for two years for her sin—to attempt suicide was at the time both a mortal and a criminal offense—there came an end to that too, and fortunately before she had altogether lost her looks.

My grandfather taught Emma’s great grandchild the violin at the New York conservatoire, which is how I happen to know the truth of the matter. Perhaps the story has become garbled through the generations, for certainly the timescale is a little strange: but the fictional universe has its own rule as it brushes up against our own. I am happy enough to accept the family version.

Flaubert, having dismissed Emma to the grave, in an elaborate coffin which her husband Charles could ill afford, chose to visit unmitigated disaster on the whole Bovary family. The debts Emma had incurred in life had to be met by Charles in what remained of his, and he was left in penury.

His eventual discovery of Emma’s love letters to Leon and Rodolphe upset him dreadfully—the maid Felicite having already badly damaged his faith in human nature by stealing all Emma’s clothes and running off with them—and the poor man died of grief. Emma’s little girl Berthe, orphaned, went to live with her grandmother, and on the old woman’s death ended up working in a cotton mill, and that was the end of the Bovarys.

The version handed down by my family is far more benign. After poor Emma went to prison in Rouen, Charles visited her weekly for a time—but dressed in drab as she was, her hair pulled back and greasy, her skin still blotchy from the effects of arsenic—his adoration for her quickly waned, and his visits became infrequent and then ceased.

The servant Felicite, far from stealing Emma’s clothes, simply wore them around the house to keep Charles happy, and was very soon replacing Emma in her master’s bed. There is some reason to believe that Felicite’s affair with Charles had been going on secretly for some years, and under Emma’s nose.

Charles had more or less pushed Leon and Rodolphe into Emma’s arms and this is a sure sign of a guilty man. But perhaps it was no bad thing. Felicite made a gift of her considerable savings to Charles and financial disaster was replaced by prosperity. Under the girl’s solicitous care little Berthe bloomed and was happy. Nor was the village unduly censorious.

Although Charles found Emma plain and unappealing, the Prison Governor at Rouen did not. Much moved by Emma’s plight, he allowed her many special privileges. She ate and slept in his quarters and having a gift for sewing and a love of fabric was kept more than busy embroidering his fine uniforms. Word of Charles’s involvement with Felicite having come to Emma, she did not hesitate to accept the Governor’s offer when her prison term was up, of a boat fare to New York. He was, after all, a married man.

In New York Emma quickly found work in Lily Bart’s Hat Shop. Lily Bart, you may remember from the Edith Wharton novel The House of Mirth—most eloquently filmed in Hollywood, starring the delectable Scully from The X-Files—was the unfortunate young woman whose single act of sexual indiscretion in High Society led to her downfall. Cast out from decent company and reduced to penury, Lily, according to Wharton, was obliged to take work in a millinery shop but soon died from sheer despond.

My family assure me that Wharton’s desire for a pointed tragedy must have got the better of her—the truth, and Wharton knew it well enough, was that Lily, though she could not sew for peanuts, was good at figures and soon took over the business: far from fading away she flourished, as did the hat shop. All the rich dowagers of New York flocked to its doors to buy, as did all the tragic heroines of literature, to work.

Customers would find themselves welcomed by none other than the lovely Anna Karenina from Moscow, who had escaped her author in the nick of time, saved herself from the iron wheels of the suicide train and bought a passage to the new world. Norah Krogstad from Norway, allowed by the forward-thinking playwright Ibsen to flee from home rather than destroy herself, found the miracle came true in New York. Earning as much as man she could be at one with man. Effie Brieff from Prussia, spared the fate of social obloquy, made an excellent seamstress and quickly regained her health and youthful high spirits.

Pretty little Emma Bovary was more than happy in this company, and many were the tales of love and loss and new determination that were exchanged amongst the women, and many an account of the villainy of men. All were especially fond of Emma, who, being a most imaginative milliner found great favor with the customers, some of whom, being the wives of meat barons, scarcely knew how to arrange a scarf let alone fix a hat.

There was some small trouble amongst the workforce when on one occasion Mr. Rochester came round to buy a grey bonnet, untrimmed, for his wife, Jane Eyre, and Emma was found alone in the back room with him, choosing scarlet ribbons. But Emma, reminded that Rochester had in all probability murdered his first wife by pushing her off a roof, agreed not to pursue the matter.

Instead, the better to keep her mind off the delights of illicit love, she remembered her role as mother and sent for little Berthe. Charles and Felicite, now having twin sons of their own, were happy enough to see the girl go: she was too like her mother for comfort.

Berthe showed considerable musical talent, was enrolled in the New York conservatoire, and within the year had married Lord Henry Ashton of Lammermoor, a baritone. It is thanks to Berthe and Henry’s eldest daughter, a chatty little thing, to whom my grandfather taught the violin, that I come to know so much about Lily Bart’s Hat Shop.

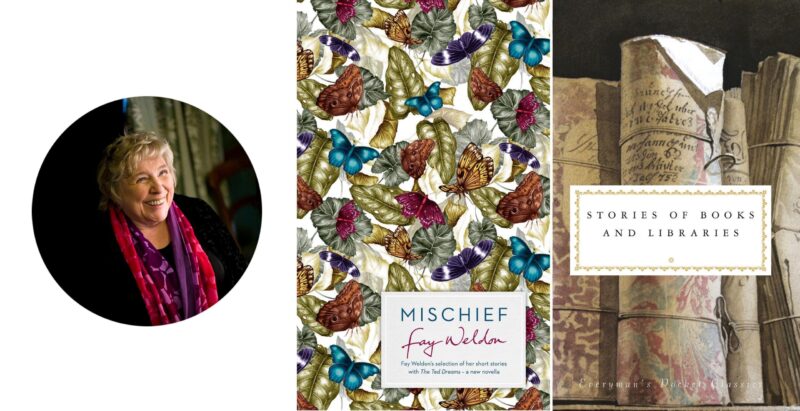

Hero illustration by Heritage Images via Getty Images