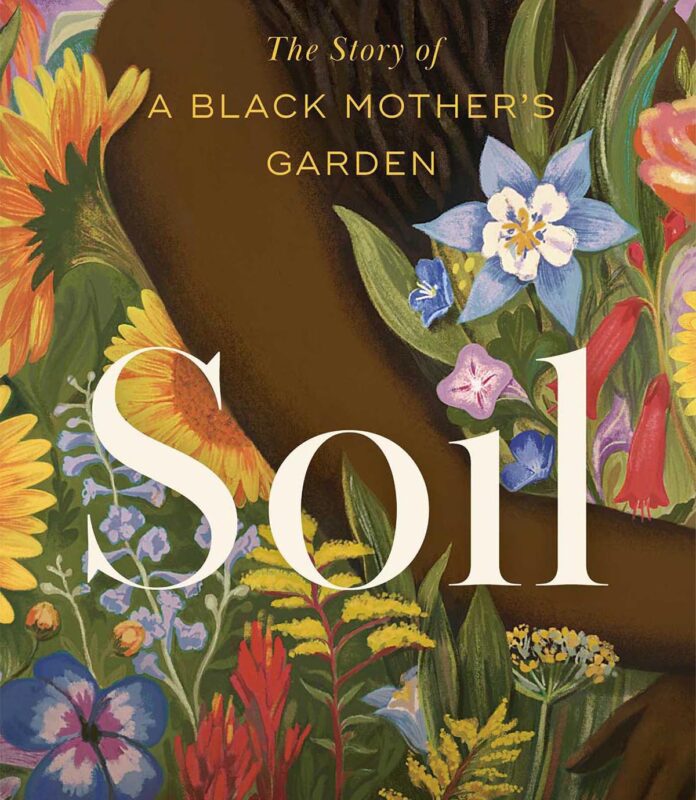

Gardening

Soil: A Love Story

How dirt under our nails brings joy to our hearts.

In 2013, Camille T. Dungy moved to Fort Collins, CO, an idyllic upper middle class, mostly white suburb where people took great pride in their homes. But that pride meant a certain uniformity, and when Dungy, an avid gardener, wanted a garden that was decidedly non-cookie cutter, she ran into local resistance. In Soil, diversification of her garden—important for its beauty, its health, and its ability to create a feeling of home—became a metaphor for the importance of diversification in the human world as well.

“Don’t you want some gloves?” Mom asked when she came by the house and found me digging in the central flower bed.

Unless I’m handling plants like the myrtle spurge, whose glue-white sap raises rashes on uncovered skin, I prefer to work with bare hands. Even writhing worms no longer repulse me.

Science provides reasons for the pleasure I feel when I dig with my hands. Microbes in the soil lower stress responses, raise serotonin levels, and may reduce inflammation in the body and brain. But when I dig, the science is not what I think about. I think about how good it feels to welcome growth.

Late-September days are perfect for putting in arrays of tulip and crocus bulbs here, tiny round black columbine seeds there. I spend warm afternoon hours on my hands and knees, digging in the soil. Some seeds I bury half an inch deep, protecting them from sharp-eyed birds. I scatter others over the surface the way wind gusts scatter dry pods’ offerings. Bulbs prefer various depths as well. Crocuses, tulips, alliums, and grape hyacinth: four inches. Mid-spring daffodils: five. Summer-blooming bearded iris: two. Savvy gardeners layer varieties of bulbs and seeds to enjoy continuous blooms.

In late summer, the big stand of sunflowers in our front yard sometimes spills over the sidewalk. I should prune the seedy three- and four-inch-diameter deadheads so they don’t block the walkway as they pull the plants down. After helping Callie with a math assignment and putting dinner in the crockpot one September afternoon, I approached the sunflowers, shears in hand. A flock of pine siskins rose from the stalks. One stayed to assess how close I might come. Saving the energy others spent on fleeing.

“It’s okay, little bird,” I whispered. “Keep eating.”

As soon as I stepped away, the flock returned to the seed-rich sunflower bed.

I didn’t know, when we chose not to use chemicals in our yard, that glyphosate, one of the main components in the weed killers the former residents preferred, disrupts serotonin uptake in animals, thus suppressing the beneficial powers of getting my hands dirty. I knew only that much of what I want to grow would be considered, by those herbicides, to be some kind of weed. Purple prairie clover, whose pen-cap-size tubular heads are ringed in seeds small as the dots on strawberries. Prairie dropseed, a mounding native grass with bursts of panicles—branched clusters of flowers from which drop the plant’s popcorn-scented seed. Monarda, sometimes called bee balm, draws many flying creatures in addition to bees. It makes me happy to see these plants coming up, sometimes willy-nilly, throughout the yard. I am happier still encountering the community of life that visits. The long-horned sunflower bee (Svastra obliqua) that looks like a stretched-out European honeybee with extra-long antennae. The white-shouldered bumblebee. The plainer Bombus nevadensis and Bombus occidentalis. Also Bombus centralis and Bombus huntii—bombastic black-, yellow-, and orange-striped native bumblebees. Goldfinches, dragonflies, rabbits, pine siskins. Learning all these names took me years. Learning a name for the joy of this grounding may take a lifetime.

A delicate larkspur, called Nuttall’s larkspur, grows in clusters near the snapdragon. I love that little flower. Several bluish, purplish starfish, each with a dark tail, like a spur, bob off the plants’ light green branches. All winter, I look forward to clusters of these blue-purple flowers returning to patches around the yard in the spring.

I don’t keep cattle, to whom Nuttall’s larkspur can be toxic. This helps explain why I am not bothered to see it on my land. I would rather foster the larkspur’s growth than treat it as an injurious plant. Cattle ranchers also list as undesirable the mint-green shrubby stalks of rabbitbrush I cultivate in our yard. And the low- growing white flower some call locoweed, which is said to drive cattle crazy. Also swamp and showy and western whorled milkweeds, with pods that split and scatter cotton-tailed seeds far and wide. Though they are native to this landscape, these plants interfere with commerce and often show up on lists of undesirable weeds. Walking her daughter to my door, the mother of one of Callie’s friends stopped near our milkweed’s rowdy pinkish flowerheads. “I got rid of so much of that when I was a kid on the farm,” the woman said.

I showed my father our brilliant yellow-flowered rabbitbrush once, pouting about seeing the plant listed in a book called Weeds of the West—a catalog that also sweeps into its pages Nuttall’s larkspur, locoweed, and all those varieties of milkweed.

“A weed,” Dad said, “is a plant that is growing in a place or a way you don’t want it to grow. That’s all that word means.”

The page in the weed book that listed Rocky Mountain iris reinforced my hesitancy to call a weed a weed. Rocky Mountain iris is indigenous to this region. It comes up in gardens as well as along trails. Rising from weathered soil like a purple flag—some call it the blue flag iris—its white- and yellow-tongued mouth opens along with my rising excitement for spring and summer’s blooms.

Synonyms for wild include: natural, undomesticated, savage, desolate, uncultivated, unbroken, uncontrolled, impractical, disorderly, rowdy, ill advised, waste. Blue flag iris doesn’t work well in bouquets. Cattle shouldn’t eat them. Their blooms don’t last long in the garden. Still, I welcome the blue flag irises’ ephemeral upheaval each June. I cheer when their blades push aside soil.