Literature

“We’ll print it if it’s the last effort of our lives”

How two American women braved U.S. censorship laws to publish James Joyce’s Ulysses.

It’s been 100 years since Ulysses was first published in Paris. Originally censored in England and America for obscenity, James Joyce’s masterful homage to the Odyssey possessed an unrivaled new style, prose, and structure that established it as one of literature’s most important 20th-century works.

Recognizing the importance of this literary milestone, the Morgan Library has pulled together seminal manuscripts and journals to present One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” (on through October 2). Yet the book might never have achieved its place in the canon had it not been for two American women and their obscure literary journal, Little Review.

According to Andrea Barnet’s All Night Party: The Women of Bohemian Greenwich Village, Little Review was founded in Chicago in 1914 by two women, Jane Heap and Margaret Anderson, who were also lovers. It had no advertising, no money to pay contributors, and frequently printed material considered so outré, no one else would publish it.

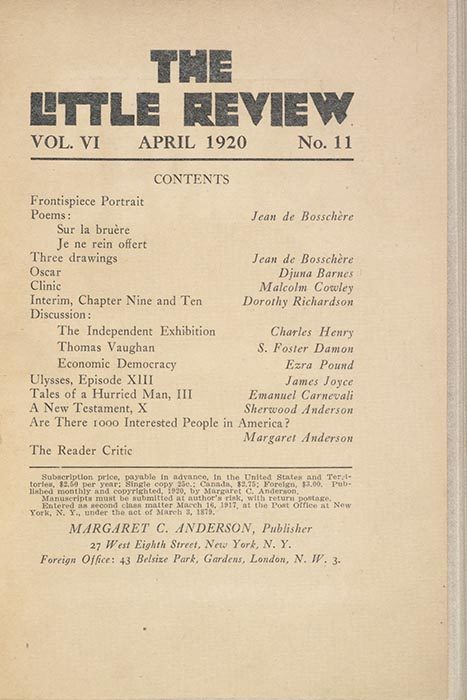

Ezra Pound, who came on as Little Review‘s Paris Editor in 1917, fondly called it “an insouciant little pagan paper.” It would go on to publish many of the great modernist authors of the 20th century until its last issue, in 1929. It also serialized Ulysses in the U.S. at a time when censorship ran rampant.

Perhaps credit for that creative daring can be laid at the feet of Anderson, a woman Pound once described as the only editor in America who “ever held the need of, or responsibility for, getting the best writers concentrated” in a single periodical.

The magazine moved to the center of Bohemian life in Greenwich Village in 1917, where it occupied four spacious rooms above an undertaker’s office at 21-25 Washington Square North as well as a basement office nearby, reportedly rented for $25/month.

Their printer, Mr. Popovitch, apparently the cheapest in New York, was sympathetic to the women. (His mother had been the poet laureate of Serbia.) But it was always touch-and-go whether the magazine would come out at all. At one point Anderson declared, “We may have to come out on tissue paper pretty soon, but we shall keep on coming out!”

As a result of the women’s dedication, the Little Review became recognized as one of the most important outlets for avant-garde literature in America, publishing works by T.S. Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, Yeats, Ford Maddox Ford, Hilda Doolittle (aka H.D.), and James Joyce, among other luminaries.

Pound first sent Anderson the opening chapter of a “tightly written manuscript” he highly recommended, but doubted she’d want to go through the trouble of publishing. At the time, U.S. Post Office censors were known to scour Little Review issues for “advanced intellectual smut.” Anderson would find it disheartening, after working hard on an issue, to receive one of the government’s dreaded white cards stating, “BURNED.”

But Pound underestimated Anderson, who immediately understood the greatness of Ulysses. “This the most beautiful thing we’ll ever have,” she told Jane. “We’ll print it if it’s the last effort of our lives.”

Between 1918 and 1920, the Little Review printed Ulysses in monthly installments, despite the fact that four separate issues were burned for alleged obscenity. In all, Anderson and Heap succeeded at publishing 13 of 18 of Joyce’s chapters before officials seized the magazine.

When they published the famous “Nausicaa” episode (Episode XIII) in April 1920—in which an erotic fantasy leads to a moment of autoerotic release (less-elegantly referred to by Anderson as the scene “where the man went off in his pants”)—the censors swooped in and arrested both women on charges of obscenity.

According to Barnet, the ensuing trial had quite a few Dada-esque moments of absurdity. For one, the judge wouldn’t allow Ulysses’ “libidinous” sections to be read aloud because it would be too much for the innocent-looking Anderson to hear. “But she is the publisher,” countered her lawyer, John Quinn.

Eventually the women were found guilty and fined $100.

There would be no regrets. As Anderson described in her memoirs: “First precise thought: I know why I’m depressed—nothing inspired is going on. Second: I demand life be inspired every moment. Third: the only way to guarantee this is to have an inspired conversation every moment. Fourth: most people never get so far as conversation; they haven’t the stamina. … Fifth: if I had a magazine I could spend my time fulfilling it with the best conversation the world has to offer. Sixth: marvelous idea… Seventh: decision to do it.”

One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” is on at the Morgan Library until October 2nd.

Hero: Portrait of James Joyce in 1928 by Berenice Abbott (1898-1991). Photo courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum