First Person

How Did We Get Here?

A renowned historian—and descendent of royalty—is concerned about the state of the world.

Noted historian Peter Frankopan shared a preview of his upcoming talk on where we’ve come from and where we’re going with Digital Party. For the rest, join the award-winning author and charismatic speaker next Tuesday night at Bartholomew Church or online (the event will also be livestreamed).

“It is usually difficult to feel the wheels of history turning—even if that is what they are always doing. Even rapid changes can feel surprisingly normal, and melt into the past.

When I finished my undergraduate studies 30 years ago, none of our parties were organised by email; no one took selfies to mark the rites of passage; and if you wanted to meet people for a drink to celebrate, you agreed on a time and a place—and were stuck with it, with no chance to send a quick message to say you were running a few minutes late.

Those were the heady days of the 1990s, a time that now feels like it was another age. Thirty years ago, China was one of the poorest countries on earth, a sleeping giant that would one day awake and shake the world with its roar (in words often attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte); the Soviet Union had collapsed, dissolving into fifteen independent states, with three—Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine—becoming the first nations in history to give up their nuclear weapons. The Cold War was over. The world seemed filled with hope, with peace and with opportunity to build a better future.

Things look very different today. China has become an economic, military and political superpower that many in the United States are convinced not only will become a major competitor but became such a long time ago. Efforts to bring security to Afghanistan, Iraq and the Middle East produced results that were mixed, and in some cases counter-productive.

Globalization helped spur growth, especially in the developing world, but came at a price that few thought—especially in terms of climate impact, sustainability and pollution. All but four of the most polluted cities on earth are now in Asia as factories manufacturing goods and products belch out fumes that risk turning the planet into a tomb for future generations, rather than an earthly paradise.

All of these changes took place while we were numb to the engines of change, or to their consequences. Rather like suddenly waking up having fallen asleep at the wheel of a car in the fast lane to find the vehicle moving at 90mph, there are two different things to do: First, to take urgent action to avoid imminent disaster; and then to spend some time thinking about how and why we dozed off in the first place.

It is one of the jobs of historians to do the latter—to explain, contextualize and work out how we got things so wrong.

How did we spend most of the last three decades thinking that Putin and the group that has been around him for decades would behave like well-mannered members of the club that would respect its rules? How did we fail to think about exits from Iraq and Afghanistan? How did China suddenly appear so fast in our rear-view mirror, seemingly from nowhere? How could we have failed to do more to deal with emissions, especially after the Kyoto Protocol of 1992 that warned of nightmarish scenarios that have since kept on getting worse? What else have we missed and are getting wrong?

Much of the problem lies in a formidable human quality, namely the ability to adapt. We don’t stop to think because we take things in our strides, to the point that toddlers now master swiping screens before mastering complex speech—something not a single one of our ancestors would ever have done.

Part of the problem too lies in the rush and pace of everyday life, where we each have our own fish to fry and things to think and worry about, our own friends and families to love, to think about how any of these big, abstract changes actually affects us individually. So we can be aware of change without linking how it affects us.

But some of the problem lies in the way we are disengaged with parts of the world where challenges and opportunities are at their most acute. The fishbowl that we live in, in the West, is both small and exceedingly comfortable.

One can go for days without coming across a single story in mainstream media about any state in Africa, let alone any region within a vast continent that is second only to Asia in size, and home to almost three times as many people as North America. Few know that Indonesia, with a population of almost 300 million, is one of the most vibrant hi-tech economies in the world. Even India, with its celebrated history stretching back thousands of years, remains a mystery to all but the most intrepid travelers and curious minds.

All these gaps are a problem at a time of major global transformation, the scale of which was profound because of technological, economic and climatic change and has now become seismic because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov put it ‘this is not about Ukraine at all, but the world order. The current crisis is a fateful, epoch-making moment in modern history. It reflects the battle over what the world order will look like.’

As someone who works on Russia, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Middle East and the Silk Roads linking Asia from north to south and east to west, it is hard to overstate the significance of the chain of events that have been set in motion by Vladimir Putin’s decision to attack Ukraine—the effects of which stand comparison to some of the landmark dates in history, from 1492 to 1939.

I’ll touch on some of these on Tuesday at the third (and last) of the Thalia Potamianos Lectures that I am giving at St Bartholomew’s Church in New York City, where I will be talking about global futures. In previous talks, I’ve gone back to moments in the past that offer important viewpoints to see how those wheels of history have turned before and to see how scholars like Aristotle and Anna Komnene have assessed change.

Do please come along if you are free, and to hear the brute noise of transitions in the 21st century that make the world of 30 years ago feel like a deep and distant memory.”

World-renowned historian and award-winning author Dr. Peter Frankopan is presenting “Global Greece: A History” for the inaugural Thalia Potamianos Lecture Series hosted by the Gennadius Library. His final lecture will be held at St. Bartholomew’s Church in New York City on Tuesday, May 10, 2022, at 6:00 p.m. You can also join the livestream, here.

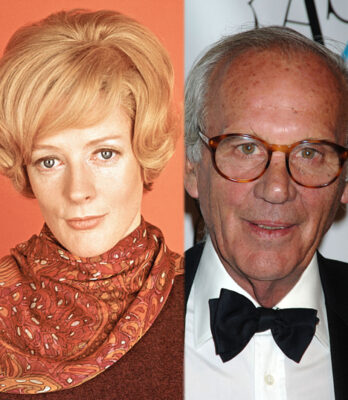

Peter Frankopan: Photo by David Levenson/Getty Images